© Copyright 2004 by AELE, Inc.

Contents (or partial contents) may be downloaded,

stored, printed or copied by, or shared with, employees

of

the same firm or government

entity that subscribes to

this library, but may not be sent to, or shared with others.

A Civil Liability Law Publication

for officers, jails, detention centers and prisons

ISSN 0739-0998

Cite this issue as:

2004 JB Mar (web edit.)

Click here to view information on the editor of this publication.

Return to the monthly publications menu

Access the multi-year Jail & Prisoner Law Case Digest

Report non-working links here

Some links are to PDF files

Adobe Reader™

must be used to view content

First Amendment

Mail

Medical Care (2 cases)

Prison Conditions: General

Prisoner Assault: By Inmates

(3 cases)

Prisoner Suicide

Private Prisons

Religion

Work Release

Access to Courts/Legal Info

Defenses: Statute of Limitations

Disability Discrimination: Prisoners

DNA Tests

First Amendment

Inmate Funds

Inmate Property

Medical Care (2 cases)

Medical Care: Mental Health

Prison Litigation Reform Act: Filing Fees (3 cases)

Prisoner Classification

Prisoner Discipline (2 cases)

Religion

Segregation: Disciplinary

Sexual Assault

Sexual Discrimination

Strip Searches: Prisoners

Telephone Access (2 cases)

Transsexual Prisoners

Workers' Compensation

•••• EDITOR'S CASE ALERT ••••

Federal appeals court reinstates prisoner's claim that he was determined to be a prison gang member in retaliation for his jailhouse lawyering activity in pursuing grievances on behalf of himself and other inmates, in violation of his First Amendment rights. Evidence used had been found insufficient during two prior investigations of suspected gang affiliation.

A California prisoner claimed that when he was "validated" by prison officials as a prison gang affiliate in retaliation for his jailhouse lawyering, and on the basis of insufficient evidence of any actual gang affiliation. He asserted that this violated his Fourteenth Amendment rights to due process and equal protection, and his First Amendment right to file prison grievances.

The prisoner is serving a life sentence and alleged that he was investigated for prison gang affiliation on three occasions. During the first investigation of his alleged association with the Black Guerrilla Family (BGF), an investigator found evidence from a confidential informant and other information insufficient to validate him as a BGF member. A second investigation the following year also found the evidence insufficient.

Two years later, he was placed in administrative segregation for a month for committing a battery on another inmate. During that time, he filed a series of grievances regarding allegedly inadequate prison conditions on behalf of himself and other inmates. When his one-month term expired, he was retained in administrative segregation pending a third investigation of his alleged affiliation with the BGF.

An investigator subsequently allegedly told the prisoner that he was being validated as a BGF member on the orders of "higher-ups," in retaliation for his having filed the grievances. The evidence used to make the validation was allegedly the same evidence that had been found insufficient to prove gang affiliation during the two prior investigations. As a result, he was placed in an indeterminate confinement in a security housing unit.

Upholding the rejection of the prisoner's due process and equal protection claims, a federal appeals court found that the plaintiff prisoner was provided adequate due process on his validation as a gang member so long as there was "some evidence" to support the determination. "Clearly," the court noted, there was some, including a report from the Los Angeles Sheriff's Department that he was a gang member and information from a confidential informant who identified him as a BGF "shot caller," as well as a probation report noting that his co-defendant on his underlying conviction was also validated as a member of the BGF. Additionally, since he was provided with the same level of due process afforded to other suspected gang members, there was no equal protection violation.

The appeals court reached a different result, however, on the First Amendment claim that he was validated as a gang member in retaliation for his filing of several grievances. It found that there was a genuine issue of material fact as to the prison officials' intent in initiating the most recent validation investigation.

There was the "suspect timing" of the validation--coming soon after his success in the prison conditions grievances, as well as the fact that the same evidence had previously been found insufficient to reach a finding of gang affiliation. While not "conclusive or retaliatory motive," the court found, it tended to show that the validation "was not motivated by any recent gang activity" on his part.

The appeals court also stated that the "some evidence" standard was insufficient to defeat the unlawful retaliation claim. While prisons have a legitimate penological interest in stopping prison gang activity, if, in fact, the defendants "abused the gang validation procedure as a cover or ruse to silence and punish" the prisoner because he filed grievances, they could not assert that the validation "served a valid penological purpose, even though he may have arguably ended up where he belonged." Summary judgment on the retaliation claim, therefore, was inappropriate.

The appeals court rejected, however, the plaintiff prisoner's request for declaratory or injunctive relief that the evidence relied on was unreliable and does not establish gang membership, and that as a matter of due process the prison officials should be enjoined from relying on this information in the future.

While the prisoner might be entitled to money damages on the retaliation claim if he prevailed at trial, the prison:

cannot be foreclosed from using the same evidence in the future in connection with his continuing imprisonment. Nor will we provide any declaration regarding Bruce's affiliation or non-affiliation with the BGF.

The defendants were not entitled to qualified immunity on the retaliation claim, since the prohibition against retaliatory punishment is clearly established law, the appeals court concluded.

Bruce v. Ylst, #01-17527, 351 F.3d 1283 (9th Cir. 2003).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Federal appeals court rules that prison's requirement that books received from vendors have special shipping labels attached or else not be delivered to prisoners unduly burdened inmates' First Amendment rights. Policy was unreasonable and arbitrary, as it was applied to packages of books and other publications but not to other packages that could just as easily contain contraband.

A prisoner housed in a security housing unit at a California state prison complained about an "operational procedure" adopted by the facility intended to prevent inmates in the unit from receiving contraband. The regulation adopted involves a "special purchases program" covering incoming property, including books, periodicals, magazines and calendars." It states that such items may be ordered by prisoners in the unit from mail order stores or publishers, provided that "approved book labels" are attached before the items are shipped.

The prisoner is required to sign the label form to receive the item and the form must also be signed by a designated prison staff member. The book label must also have a vendor stamp attached. Packages without the vendor stamp, label, or the required signatures are returned to the sender, and all property items must be ordered from an "approved vendor." The procedure also provides that an inmate may receive only one book package per month, and may possess no more than ten books and magazines at any one time.

The plaintiff prisoner had a friend who placed an order with Barnes & Noble Booksellers for four books to be shipped to him. She included the necessary required book label with her order, but two months later, the prisoner had not received the books. Upon inquiry, the friend was told that in that two month period, over one hundred book packages were returned to sender because of the vendor's failure to place the book label on the box, or because the vendor did not place its vendor stamp in the appropriate box on the label. The prisoner received the books several months later, after the friend took the label form to the bookstore to ensure its proper completion.

The trial court agreed that ensuring that books are shipped directly from a publisher and preventing the introduction of contraband into the prison were legitimate penological interests. It noted, however, that the policy was not "neutral," i.e., it was not unrelated to the suppression of expression. The court pointed to the fact that the label policy applied to packages of books, but did not apply to packages containing other items, such as tennis shoes, thermal tops and bottoms and approved appliances.

Additionally, since all personal property received by inmates in the mail, including books and magazines, are searched prior to delivery to the prisoner, the defendants failed to show any way in which the book label policy provided a "measure of security not afforded by these routine and mandatory searches." The court noted that even a legitimate package of books, including an authentic book label provided by the inmate, would be searched by prison authorities before delivery to the prisoner.

Since the book label requirement was found to be "arbitrary and unreasonable," it was not rationally related to legitimate penological objective, but instead was "unduly burdensome" on the prisoner's First Amendment rights. The court therefore enjoined the defendants from enforcing any policy prohibiting inmates from receiving books, periodicals, magazines or calendars "solely because a book label approved by the prison was not attached." The court emphasized that the order did not affect other policies requiring that book packages be shipped directly from a vendor in packages with the vendor's return address and invoice, or requiring a search of those packages, or limiting the number of packages the prisoners could receive or the type and number of books a prisoner may order or possess.

A federal appeals court has upheld this result, agreeing that the policy in question was not rationally related to the prison's asserted interest in security and order, and therefore violated the prisoner's First Amendment rights.

The district court did not err in concluding that the book label requirement is not rationally related to a legitimate penological objective. The requirement that books be sent from approved vendors, the policy of searching all incoming packages, and the lack of a vendor label requirement for items such as shoes, clothing, and appliances support the conclusion that the book label policy is not rationally related to the need to prevent the introduction of contraband. The injunction granted by the district court is not overly intrusive and is closely tied to the identified violation.

Ashker v. California Department of Corrections, #02-17077, 350 F.3d 917 (9th Cir. 2003).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Five-hour delay in transporting detainee to hospital after he repeatedly complained of chest pain did not render jailers liable for his death twelve hours after hospitalization, in the absence of any evidence that the defendants actually perceived or had knowledge of a "substantial risk" of serious harm.

A motorist was arrested and taken into custody on a traffic offense and allegedly complained of chest pains soon after he was booked and placed into a holding cell. Officers in charge of his confinement allegedly waited over five hours before arranging to have him transported to a nearby hospital. Once there, he died approximately twelve hours later.

The detainee's estate claimed that the death was caused by an unlawful municipal custom, policy, or practice, and that these actions constituted deliberate indifference to the detainee's serious medical needs. The decedent allegedly had repeatedly stated that he was suffering chest pains during the five-hour period before he was taken to the hospital, and periodically clutched his chest, appearing to have a "light sweat."

An autopsy revealed that the detainee died from arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease. It also showed that cocaine abuse was present and may have contributed to the death. The defendants in the estate's federal civil rights lawsuit disputed whether the decedent had immediately complained of chest pain, or whether he did not vocally do so until he had already been in custody for almost five hours.

Regardless of this, a federal trial court ruled, the record in the case failed to demonstrate "deliberate indifference" to the detainee's serious medical needs. Deliberate indifference, the court noted, must be based on both an objectively serious medical need and a subjective knowledge of a substantial risk of serious harm to the prisoner's health and safety which the defendants disregard.

The court noted that the defendant city and its officers did not altogether deny medical treatment to the detainee, but rather delayed it for several hours. In order to show that this rose to the level of a constitutional violation, the court commented, the plaintiff had to place "verifying medical evidence in the record to establish the detrimental effect of the delay in medical treatment."

In this case, the court found, the medical records from the hospital did not demonstrate any such detrimental effect, as they indicated that the detainee's condition had stabilized soon after he arrived at the hospital, and that they died following a relapse nearly twelve hours later. Nothing in the records, the court stated, suggests that the detainee's death could have been avoided if he had received more prompt medical treatment.

Even if the detainee's subjective feelings of pain, worry, and anxiety which he may have experienced from the delay qualified as objectively serious enough to satisfy the objective part of the test, the court continued, there was nothing that showed that the detaining officers "knew of and disregarded a substantial risk of serious harm" to his health and safety. There was no evidence that any of the officers "actually perceived this risk." There was no evidence that the detainee was taking heart medication, for instance, or that any detaining officer or even the detainee himself was aware of a pre-existing heart condition which, when combined with complaints of chest pain, "might have warranted greater diligence or scrutiny." Accordingly, the officers could not be said to have acted with deliberate indifference in delaying the prisoner's transport to the hospital.

Joseph v. City of Detroit, 289 F. Supp. 2d 863 (E.D. Mich. 2003).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the AELE website.

•Return to the Contents menu.

Even if jail medical personnel were deliberately indifferent to insulin-dependent diabetic's serious medical needs by giving him only one insulin shot over a 48 hour period--when he normally received up to four shots per day--the county sheriff's office could not be held liable in the absence of an official policy or custom causing the deprivation.

An insulin-dependent diabetic in Florida sued the county sheriff's office, claiming deliberate indifference to his serious medical needs based on the claim that he was provided with only one shot of insulin during a forty-eight hour period while he was in a county detention facility as a pre-trial detainee. He normally receives up to four shots of insulin per day to maintain his blood sugar at a safe level, he argues, and he allegedly required hospitalization for three days after his release as a result of the prior denial of medication.

Granting summary judgment for the defendant, the trial court reasoned that even if the plaintiff could show that jail officials had been deliberately indifferent to his serious medical condition by giving him only one shot of insulin during the period in question, the county sheriff's office could not be held liable for a violation of his constitutional rights. In a federal civil rights claim, the doctrine of vicarious liability, making an employer responsible for the actions of employees carried out within the scope of their employment, does not apply.

Rather, liability requires a showing that a constitutional violation was caused by an official municipal policy or custom. No such policy or custom was shown to have caused the treatment decisions by the nurses at the jail. The nurses were not "policy-makers" possessing final authority to establish policy with respect to the care of pre-trial detainees at the jail, but were rather "not free" to ignore any official sheriff's office policies. They were also not free from review or supervision of the responsible doctor.

There was a dispute as to when the prisoner's blood sugar was tested, and the adequacy of the care provided. But given the absence of an official policy or custom leading to the alleged deprivation of insulin, these facts were not ultimately dispositive of liability.

The plaintiff prisoner had submitted "absolutely no medical opinion or proof" that the delegation of routine nursing tasks was in any way contrary to the "express policy of the Brevard County Sheriff's Office that every inmate receive quality medical care throughout his incarceration and never be denied needed medical care."

Engelleiter v. Brevard County Sheriff's Department, 290 F. Supp. 2d 1300 (M.D. Fla. 2003).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the AELE website.

•Return to the Contents menu.

Two prisoners, confined for 24 hours in an "unsanitary" isolation cell designed for one prisoner in which a clogged floor drain resulted in feces and urine remaining on the cell floor, could not recover damages for mental or emotional injuries in the absence of a prior physical injury.

Two Mississippi state prisoners sued correctional officials for alleged unconstitutional conditions of confinement. They complained about their placement for twenty-four hours in an allegedly unsanitary isolation cell after they were involved in an altercation with two prison guards. The isolation was imposed as administrative segregation after they were both charged with simple assault of an officer.

The isolation cell was a "sparse eight-by-eight concrete room, meant to house one person." There is no running water and no toilet in the room, with the only sanitary facility being a grate-covered hole in the floor which can be "flushed" from outside the room. The only "bed" in the cell is a concrete protrusion from the wall wide enough for one person, with no mattress, sheets, or blankets.

While the prisoners conceded that the cell was clean and dry when they arrived, they contended that feces soon obstructed the hole, and that when they tried to push the feces down the drain with a piece of a paper plate, this further clogged the drain. When they subsequently attempted to urinate, the clogged drain caused their urine to splatter onto the cell floor, and at one point, one of them became nauseated from the smell of the sewage and vomited into the drain.

The prisoners claimed that they repeatedly requested help from the guards, who did attempt to flush the drain, but this did not work. Finally, one guard instructed an inmate trusty to spray water into the cell through an opening at the bottom of the ell door.

This, unsurprisingly, did not unclog the drain. Instead, it spread the sewage throughout the cell. [They] allegedly requested a mop to clean up the mess, but their request was denied. They contend that they were never given any cleaning supplies.

The prisoners ate lunch and dinner in the isolation cell, and since the cell had neither running water nor soap, were not able to wash their hands before eating. They also were allegedly given no utensils to eat with. The prisoners were dressed only in boxer shorts and their requests for a mattress or blanket were denied. They therefore shared the small concrete slab and attempted to sleep. While the cell is equipped with heat, they claimed that it was uncomfortably cold that night.

Upholding the dismissal of the prisoners' claims, a federal appeals court noted that under 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1997e(e), inmates cannot recover damages for mental or emotional injuries in the absence of a prior physical injury. Here, any "physical injury" was extremely minimal. The only claimed physical reaction, nausea suffered by one prisoner, was not severe enough to warrant medical attention, the court stated.

Alexander v. Tippah County, Mississippi, No. 02-61033, 351 F.3d 626 (5th Cir. 2003).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Detainee who was in the process of bonding out of a county jail when he was attacked by other inmates and injured was still an "inmate" for purposes of a Mississippi state statute providing governmental entities and employees immunity under state law for injury claims by prisoners. State Supreme Court also rules that an exception to governmental immunity for wanton or reckless disregard by a governmental employee does not apply to claims by prisoners.

A Mississippi man arrested for allegedly shooting and injuring someone was held in a county jail for several days, before he met with a bail bondsman in an effort to secure his release. After meeting with the bondsman and while waiting for his mother to arrive with the necessary funds, the detainee went to retrieve his personal items from his cell. He later asserted that he had reported to a deputy that he had been threatened by his alleged victim's brother, who was a jail inmate at the time.

Once in the cell area, the detainee was attacked by several inmates. After the fight was broken up, his mother arrived with the money, the necessary paperwork was completed, and he was released from the county jail, going directly to a hospital where he was admitted and treated for internal bleeding, losing his spleen in subsequent surgery.

The injured detainee sued the county, the sheriff, and several employees of the sheriff's department in state court for alleged failure to protect him from the assault.

Upholding summary judgment for the defendants on the basis of governmental immunity, the Supreme Court of Mississippi found that the detainee, while he may have been in the process of bonding out of the jail, was still an "inmate" at the time of the attack for purposes of a state statute which provides that governmental entities are exempt from liability for claims brought by prisoners. The county sheriff's department was therefore immune from the detainee's claims for damages under Mississippi Code Sec. 11-46-9(1)(m).

The court noted that although the detainee had signed all documents which were required to complete the bonding process, he was still waiting for his mother to arrive with the money needed to release him, and the bonding company agent had not yet completed the bond and presented it to the sheriff for approval. In short, he was still an "inmate" because he was not yet free to leave the jail when the attack occurred.

The court also ruled that an exception to the statute for "wanton and/or reckless disregard" by a governmental employee, which results in a waiver of governmental immunity, did not apply. This exception, the court held, does not apply to claims by inmates, since the legislature has clearly indicated an intent to make governmental entities in Mississippi exempt from all claims arising from claimants who are inmates at the time the claim arises.

While we are not unsympathetic to Love's injuries and resulting damages, we are on the other hand bound by our case law and by clear legislative intent in the enactment of the MTCA [Mississippi Tort Claims Act, the statute providing governmental immunity from claims by inmates], which provides [...] that a governmental entity and its employees, when acting within the course and scope of their employment, shall not be liable for any claim made by one who at the time of the cause of action is a jail inmate. Love was without question an inmate of the Sunflower County Jail at the time of this unfortunate attack by fellow jail inmates.

Love v. Sunflower County Sheriff's Department, No. 2002-CA-01724-SCT, 860 So. 2d 797 (Miss. 2003).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Correctional officers could not be held liable for prisoner's injuries from stabbing by his cellmate. Their awareness of cellmate's plans to "fake a hanging" and statement that the prisoner would help him "one way or another" did not provide them with specific knowledge of a particular threat of assault as required to show deliberate indifference to a serious risk of harm.

A Georgia prisoner serving a life sentence was classified as a medium-security prisoner with no history of violence while in prison. After prison officials learned of alleged inappropriate use of a library computer where the prisoner was assigned to work, he was questioned as part of the investigation and was placed on involuntary administrative segregation when he failed to fully cooperate with the investigation.

He was placed in a cell with a cellmate who was pending reclassification to maximum-security status. He asked not to be placed there, but this request was denied. The cellmate told him of his intention to "fake a hanging," as part of a plan to be transferred to the medical prison. The prisoner refused to assist his new cellmate's plans and the cellmate then informed him that he would help "one way or another."

The prisoner interpreted this as a verbal threat. His cellmate allegedly also paced the cell like a "caged animal," threatening correctional officers and orderlies, and generally "acting in a disorderly manner." The prisoner allegedly communicated with two correctional officers, telling them that his cellmate was "acting crazy" and planned on faking a hanging. He also told of his cellmate's comment that he would help in the faked hanging "one way or another." Despite this, the prisoner was told that no removal from the cell would be in order for him until the library computer investigation came to an end.

His cellmate subsequently assaulted him, stabbing him in the stomach with a "shank" (an inmate-made weapon).

The injured prisoner sued the two correctional officers for failing to protect him against the assault.

A federal appeals court has upheld summary judgment for the defendants. It found that the officers, while they may have had a "generalized awareness" of the cellmate's conduct, and that he was a "problem inmate" with a well-documented history of prison disobedience and had been prone to violence, they did not clearly know that the cellmate had specifically threatened to the plaintiff prisoner.

The plaintiff prisoner never told the defendant officers that he feared his cellmate or that the cellmate had clearly threatened him. His complaints about his cellmate acting "crazy," wanting to stage a fake hanging, and making the statement that the plaintiff would help him "one way or another" were not specific enough, the court found, to constitute awareness of the plaintiff's fear or of a "particularized threat."

Having failed to show that the officers acted with "deliberate indifference" to a known risk that he would be assaulted by his cellmate, the plaintiff prisoner could not recover damages from them for his injuries.

Carter v. Galloway, No. 02-16635, 352 F.3d 1346 (11th Cir. 2003).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Prisoner could not succeed in suing correctional officials for allegedly failing to protect him from assault by another inmate who he was convicted of murdering. Appeals court rules that any injuries plaintiff prisoner suffered, including his conviction and subsequent placement in solitary confinement, were the result of his "affirmative act of murder," rather than any failure on the part of the defendants.

A New York prisoner sued correctional officials for allegedly violating his Eighth Amendment rights by failing to protect him from another inmate whom he was later convicted of murdering, as well as claiming that they violated his due process rights by placing him in solitary confinement after his conviction, without a proper hearing and based upon the insufficient evidence at his murder trial.

The prisoner's claims stemmed from events relating to two fights between him and the other prisoner. While he claimed that he was defenseless against the prisoner's first attack in June of 1996, he was eventually convicted of stabbing the prisoner to death during the second assault two months later, and then sentenced to ten years in solitary confinement. His lawsuit claimed that prison officials were aware of how dangerous the other prisoner was, but that they neither separated him from the general prison population nor responded to the plaintiff's letter request for protection from him.

Upholding summary judgment for the defendants, a federal appeals court agreed that the "indisputable fact" that a jury convicted the plaintiff of second-degree murder was "conclusive against him on the Eighth Amendment claim," and that his injuries were caused by his "aggression" against the decedent and subsequent murder conviction, not by the defendants' failure to protect him.

The plaintiff, the court found, suffered "no actual injury" from the defendants' alleged failure to provide him protection from the prisoner whom he murdered.

All of his alleged injuries stemmed from his affirmative act of murder, rather than any failure on the part of the defendants. Moreover, this court is precluded, under Heck v. Humphrey, 5122 U.S. 477 (1994), from providing Encarnacion [the plaintiff] the result he seeks: essentially, a reversal of his murder conviction, and release from solitary confinement, in addition to monetary damages.

Encarnacion v. Dann, #02-0312, 80 Fed. Appx. 140 (2nd Cir. 2003).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the Internet.

•Return to the Contents menu.

Georgia county correctional facility personnel took steps to monitor prisoner known to be a suicide risk after he previously attempted to harm himself and were not liable for his successful suicide in his cell which he accomplished by "unique methods," fashioning a tourniquet from a bed sheet and a crutch he had in his cell which he needed to walk after he broke his leg.

A Georgia man was discovered with second and third degree burns at his home, and was accused of burning down his house after killing his wife. He had cuts on both sides of his neck, slits on both of his wrists and several puncture wounds in his chest. He was initially hospitalized, then transferred to a facility for psychiatric treatment, and finally booked into a county correctional facility on a charge of "malice murder."

While incarcerated, he attempted to harm himself by swallowing a bar of soap, and was hospitalized for further psychiatric evaluation, after which he was again placed into the county correctional facility, with a notation on his record that he was a suicide risk. He was permanently housed in the booking area in a cell with a barred door instead of a solid door, where he was in open view and could be routinely monitored by personnel working in the area. He subsequently broke his leg and was allowed to keep a set of crutches in his cell as they were necessary for him to walk.

Days later, he committed suicide by using one of his bed sheets to fashion a tourniquet, which he placed around his neck. Using a portion of a crutch he had disassembled, he twisted the bed sheet until he asphyxiated, apparently laying down on the piece of the crutch in order to keep the tourniquet from loosening.

Just prior to the suicide, deputies checked on him several times and he appeared to be sleeping with his back to the door. He was not discovered to be dead until a nurse entered the cell in the morning to give him medication.

The prisoner's son brought a wrongful death lawsuit in state court claiming that the county and its personnel took inadequate steps to prevent the suicide. A Georgia intermediate appeals court upheld summary judgment for the defendants.

The record showed that the sheriff's department adopted procedures for caring for potentially suicidal prisoners, including housing them in an area which was manned 24-hours-a-day and where they could be visually monitored in their cells. Deputies in the area were directed to use discretion in their method and frequency of monitoring, and in the type of items that prisoners were allowed to have in their cells, and on-the-job training in such monitoring was provided.

The court found that the deputies on duty followed the department's policy by routinely and frequently monitoring the prisoner, but that he was able to successfully commit his suicide attempt due to the "unique methods" he used to keep his actions undetected, appearing to be asleep while they monitored him.

The deputies were entitled to official immunity in the lawsuit, as the question of whether they should have checked on the inmate more frequently, should have woken him, or should have taken the sheets and crutches out of his cell were issues of discretion which they had to exercise on a common sense case-by-case basis determined by the facts particular to each case. In this case, given the prisoner's burn injuries and broken leg, the deputies actions did not amount to willfulness or malice, and therefore could not give rise to liability, the court found.

Middlebrooks v. Bibb County, 582 S.E.2d 539 (Ga. App. 2003).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the AELE website.

•Return to the Contents menu.

•••• EDITOR'S CASE ALERT ••••

Prisoner's claim that his constitutional rights to adequate conditions and medical care were being violated in a private prison in Ohio where he was incarcerated under a contract with the District of Columbia, and that D.C. officials knew or should have known of this, but failed to take corrective action was sufficient to state a federal civil rights claim against the District.

A District of Columbia prisoner was incarcerated in a private prison in Youngstown Ohio which was operated by a private company, the Corrections Corporation of America, under a contract with the District. He filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the District of Columbia under 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1983 for constitutional violations he claimed to have suffered while incarcerated there, in a lawsuit in which he acted as his own lawyer.

He complained about the Youngstown facility and what happened to him there and alleged that the District of Columbia "knew or should have known" that he had been mistreated. The Complaint asserted that prison officials used common needles to draw blood from him and members of his "pod," deprived him of medication for a month, locked him down "for no apparent reason," forced him to lie on the cold floor naked between 15 to 20 hours everyday, denied him running water or toilet water in his cell for over 72 hours, sprayed tear gas in the cells and pods, and destroyed his property.

The plaintiff prisoner claimed that this mistreatment caused him to catch pneumonia, to suffer a mild stroke, and to become infected by "yellow jaundice" from the use of the common needle. He claimed that the District learned or should have learned about his situation from his own complaints to the mayor and to the Department of Corrections Director, as well as from his wife's telephone calls, newspaper articles describing the alleged mistreatment of prisoners at Youngstown, and the activities of a contract monitor appointed under a settlement of a class action brought by Youngstown prisoners against the District and the Corrections Corporation.

A federal appeals court overturned the trial court's dismissal of the lawsuit. The prisoner's assertions that, under the circumstances, the District knew or should have known of the alleged constitutional violations but failed to take corrective actions were sufficient to state a claim against the District.

While a municipality is not required to take reasonable care to discover and prevent constitutional violations, since deliberate indifference, rather than mere negligence is required for a federal civil rights claim, when faced with actual or constructive knowledge that its agents "will probably violate constitutional rights," the court stated, "the city may not adopt a policy of inaction."

If the plaintiff prisoner can prove the violations he asserted and prove as well that the District had actual or constructive knowledge of them, "he will have established the District's liability." Accordingly, the trial court erred in dismissing his complaint for failure to state a claim.

The appeals court also noted that under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 8(a), only requiring that a complaint in a federal lawsuit supply "a short and plain statement of the claim showing that the pleader is entitled to relief," the fact that the prisoner's allegations of the District's actual or constructive knowledge was "conclusory" did not matter. "Many well-pleaded complaints are conclusory."

Warren v. District of Columbia, No. 02-7120, 353 F.3d 36 (D.C. Cir. 2004).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Prison policy prohibiting inmates from purchasing Muslim prayer oils and keeping them in their cells was rationally related to a legitimate interest in deterring drug use, since the oils could mask the scent of drugs, but federal appeals court orders further proceedings under federal statute requiring a showing of a compelling state interest and use of the "least restrictive means" to justify a "substantial burden" on prisoner religious practices.

A devout Muslim prisoner in Oklahoma was, for a time, allowed to purchase "prayer oils" and use them in his cell subject to certain limitations, and this occurred, he claimed "without incident." Such "prayer oils" are used by Muslims to "enhance the spiritual value of their five daily prayers." In May of 1999, a new Oklahoma correctional policy was adopted which banned the sale of Muslim prayer oils in prison canteens and the in-cell possession and use of such oils by inmates. The prisoner filed a lawsuit challenging the policy.

Under the new policy, Muslim inmates were allowed, however, to access prayer oils through volunteer chaplains who could provide the oils for inmate use during a religious service. The chaplains were required to remove the prayer oils from the prison facilities when they left, and they were not available during each of the five daily Muslim prayers. Additionally, all inmates were still allowed to purchase "imitation designer colognes and oils" from the prison canteen and keep them in their cells. The prisoner claimed that these were not the prayer oils he used during his daily prayers because they were not prepared at the "spirit level."

A federal appeals court noted that there was no evidence that the prayer oils' chemical basis was any different from the "imitation designer colognes and oils" that the 1999 policy allowed. Subsequent tests with drug-detecting dogs determined that the "imitation" colognes and oils masked the scent of drugs and interfered with drug dogs' ability to successfully detect drugs. Therefore, in June of 2002, the policy was further changed to prohibit the sale of both Muslim prayer oils and "imitation designer colognes/perfumes" in the prison canteen or by any inmate group, or possession of the substances in inmate cells. Muslim prisoners were allowed to own a bottle of prayer oil as long as it is used and stored in designated worship areas, but the plaintiff prisoner complained that Muslim prisoners cannot access these areas five times per day.

The appeals court found that prison officials had a legitimate penological interest in preventing the use and possession of illegal drugs, as well as maintaining prison order and safety, goals to which the policies were "rationally related." Additionally, the prisoner was given some alternative avenue of praying with prayer oils, in the designated worship areas under the supervision of the outside chaplains.

The court also found that accommodating the prisoner's need to access his prayer oils five times per day would likely have "heavily burdened" prison resources and other inmates' religious interests.

The court found, therefore, that the prisoner failed to show that his clearly established rights were violated, and upheld the trial court's grant of qualified immunity to the director of the Oklahoma Department of Corrections.

The appeals court noted that neither party in the litigation had brought the attention of the trial court to the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA), 42 U.S.C. Sec. 2000cc-3, newly enacted in September of 2000, shortly after the beginning of the case. The trial court, therefore, failed to attempt to apply the legal standard in that statute to the prisoner's claims. Under RLUIPA, a rational relationship to a legitimate penological interest is not sufficient as a basis to substantially burden a prisoner's exercise of religious freedom. Rather, it provides:

(a) GENERAL RULE- No government shall impose a substantial burden on the religious exercise of a person residing in or confined to an institution, as defined in section 2 of the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act (42 U.S.C. 1997), even if the burden results from a rule of general applicability, unless the government demonstrates that imposition of the burden on that person-- (1) is in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest; and (2) is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest. (b) SCOPE OF APPLICATION- This section applies in any case in which-- (1) the substantial burden is imposed in a program or activity that receives Federal financial assistance; or (2) the substantial burden affects, or removal of that substantial burden would affect, commerce with foreign nations, among the several States, or with Indian tribes.

The appeals court therefore ordered further proceedings to determine whether the prisoner's complaint stated a claim under RLUIPA, and whether it should appoint a lawyer to assist the prisoner in presenting a RLUIPA claim.

Hammons v. Saffle, No. 02-5009, 348 F.3d 1250 (10th Cir. 2003).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the Internet.

•Return to the Contents menu.

Removal of New York prisoner from work release program violated his right to procedural due process when he did not receive advance notice of the hearing, information about the evidence to be used against him, and an opportunity to present an opposing point of view.

A New York state prisoner was accepted into the Temporary Release Program of the New York Department of Correctional Services. After fifteen months in the program, during which he was employed and spent five days at home and two days per week in a correctional facility, he was removed from the program and returned to prison full time.

This happened after he received two speeding tickets, which formed the basis of a misbehavior report charging him with a temporary release violation and false statements or information. A disciplinary hearing was held regarding the misbehavior report, at which the prisoner was present. The hearing officer relied only on the second alleged speeding ticket in finding the prisoner guilty. This hearing officer referred this result to the Temporary Release Committee (TRC) for review.

The committee held a hearing at which the prisoner was not present, and of which he was allegedly not given advance notice, and recommended that he be removed from the program for disciplinary reasons. This was carried out, and a subsequent administrative appeal of the decision was denied.

The prisoner claimed that his due process rights were violated when he was not allowed to participate in the TRC removal hearing.

A New York trial court agreed, finding that the procedure used to remove the prisoner from the program "did not comport with due process." The prisoner should have, the court held, been given written notice of the claimed violation being considered by the TRC, as well as being told about the evidence that was forwarded to the TRC to be used against him. He additionally should have been given an opportunity to present proof in opposition to this evidence in front of the TRC.

Once the state has given a prisoner the "freedom to live outside an institution," the court stated, "it cannot take that right away without according the inmate procedural due process."

The court further noted that the TRC hearing made different findings than the disciplinary hearing officer. Specifically, the disciplinary hearing officer did not find the prisoner guilty concerning the violation involving the first speeding ticket, but the TRC based its recommendation to remove the prisoner from the program on the conclusion that the prisoner "jeopardized safety of community receiving two speeding citations" while on temporary release.

The court therefore ordered a new TRC hearing on the issue of the prisoner's removal from the program.

Kroemer v. Joy, 769 N.Y.S.2d 357 (Sup. 2003).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the AELE website.

•Return to the Contents menu.

Report non-working links here

Access to Courts/Legal Info

Ohio Supreme Court deputy clerks' application of court rules to prisoner's attempted filing of an untimely memorandum in his pending appeal did not violate his right to equal protection of law, since the rules applied equally to all those seeking to pursue appeals before the court. State Ex Rel. Fuller v. Mengel, 2003 Ohio 6448, 800 N.E.2d 25 (Ohio 2003).

Defenses: Statute of Limitations

Further proceedings were required to determine whether claim by heirs of juvenile detainee who died while participating in exercises while incarcerated was barred by a statute of limitations or whether the statute of limitations for filing a federal civil rights claim was extended by their timely filing of a state law claim that arose out of the same factual circumstances. Lucchesi v. Bar-O Boys Ranch, No. 02-17079, 353 F.3d 691 (9th Cir. 2003). [PDF]

Disability Discrimination: Prisoners

Prisoner's heart condition of Prinzmetal's angina did not constitute a "disability" under the Americans with Disabilities Act, ADA, 42 U.S.C. Sec. 12101 et seq. since it did not normally limit his capacity to work. Denial of prisoner's request to transfer to prison work camp, which would allow him to earn reductions in his sentence at a faster rate, based on camp's inability to provide him with adequate medical care for his condition, did not constitute disability discrimination. Charbonneau v. Gorczyk, No. 01-312, 838 A.2d 117 (Vt. 2003).

DNA Tests

Pennsylvania statute authorizing Department of Corrections to obtain a DNA sample from an inmate while they were incarcerated for enumerated offenses, including robbery and burglary, did not entitle it to do so when prisoner's sentence for robbery and burglary had expired, and while he was serving a sentence for a different offense. Smith v. Department of Corrections, 837 A.2d 652 (Pa. Cmwlth. 2003).[PDF]

First Amendment

Wisconsin prisoner failed to show that transfer to another facility was a violation of his First Amendment rights and retaliatory for his participation in prior lawsuits against prison employees, as there was no evidence that those who authorized the transfer knew of these prior lawsuits. Johnson v. Kingston, 292 F. Supp. 2d 1146 (W.D. Wis. 2003).

Inmate Funds

Twenty percent deduction from Pennsylvania inmate's prison account to pay his criminal fine was authorized by statute and requirement that he pay small amounts for expenses such as medical visits, copying expenses, and personal hygiene supplies did not constitute cruel and unusual punishment or otherwise violate his rights. Neely v. Department of Corrections, 838 A.2d 16 (Pa. Cmwlth 2003). [PDF]

Inmate Property

Former prisoner could not pursue federal civil rights claim over personal property allegedly taken from him and not returned to him when he was released from county jail when Indiana state law provided adequate procedures for asserting claims for losses of property caused by state employees. Batchelder v. Arnold, 291 F. Supp. 2d 820 (N.D. Ind. 2003).

Medical Care

Even if prisoner suffered a serious injury when allegedly defective cell doors closed on him, he could not pursue a constitutional claim for inadequate medical care against prison officials in the absence of facts that showed that they acted with deliberate indifference in denying him such care. Burks v. Nassau County Sheriff's Department, 288 F. Supp. 2d 298 (E.D.N.Y. 2003).

Prisoner's claim that a prison official had canceled his prescribed medical treatment with a pain reliever, muscle relaxer and physical therapy on the ground that the prison could not afford the cost was sufficient to assert a claim for inadequate medical care. Wilson v. Vannatta, 291 F. Supp. 2d 811 (N.D. Ind. 2003).

Medical Care: Mental Health

Psychiatrist was entitled to summary judgment on prisoner's claim against him alleging unjustified forced administration of anti-psychotic drugs and excessive doses of one such drug, causing memory loss, headaches, twitching, and confusion. Prisoner failed to properly present expert testimony or other medical evidence sufficient to establish a claim of deliberate indifference to his serious medical needs, or that the psychiatrist had subjective knowledge that there was an excessive risk to the prisoner's health and that the psychiatrist then failed to act on the basis of that knowledge. Roberson v. Goodman, 293 F. Supp. 2d 1075 (D.N.D. 2003).

Prison Litigation Reform Act: Filing Fees

Dismissal of prisoner's civil rights lawsuit against correctional officials was justified under the Prison Litigation Reform Act, 28 U.S.C. Sec. 1915(b) for his repeated failure to make monthly partial payments towards the court filing fee. Cosby v. N.R. Meadors, No. 02-1540 (10th Cir. 2003).

Under the Prison Litigation Reform Act's rules concerning the payment of filing fees, a prisoner attempting to proceed in a federal civil rights lawsuit as a pauper could not postpone payment of the full filing fee until after he was released, and was required to make installment payments of at least 20 percent of the monthly income credited to his prisoner account until the fee was paid. Ippolito v. Buss, 293 F. Supp. 2d. 881 (N.D. Ind. 2003).

Trial court was not required to give a reason for denying a prisoner's motion to proceed without paying filing fees after prisoner failed to comply with the Prison Litigation Reform Act's requirements for a waiver of fees. Massey v. Inmate Grievance Office, No. 2229, 837 A.2d 1040 (Md. App. 2003). [PDF]

Prisoner Classification

Bureau of Prisons' application to prisoner of a statutory requirement limiting the amount of time an inmate can spend in a community confinement center to 10% of his total sentence was not a violation of his rights. The fact that the prisoner was sentenced before a Deputy Attorney General's opinion on the subject was issued did not alter the result. Adler v. Menifee, 293 F. Supp. 2d 363 (S.D.N.Y. 2003).

Prisoner Discipline

Prisoner was entitled to further proceedings concerning alleged denial of due process in disciplinary hearing when the disciplinary board allegedly refused to allow live testimony of witnesses without providing a reason for doing so, and also allegedly refused to review allegedly exculpatory evidence on surveillance videotape of incident. Ashby v. Davis, No. 02-3007, 82 Fed. Appx. 467 (7th Cir. 2003).

Alleged failure to allow prisoner to present live testimony at prison disciplinary hearing was harmless when he failed to indicate which witnesses he wanted to call or what he expected them to say, and adequate evidence supported charge that he had unauthorized sexual contact with a prison visitor. Sargent v. Knight, #02-3489, 82 F.3d. Appx. 472 (7th Cir. 2003).

Religion

Muslim prisoner adequately stated a claim against a correctional officer for violating his right to exercise his religion by confiscating his prayer musk oil from his cell when he had the prison chaplain's approval to possess the oil and he was told, in response to his grievance against the officer, that prisoners were allowed to have such oil in their cells. Baltoski v. Pretorius, 291 F. Supp. 2d 807 (N.D. Ind. 2003).

Segregation: Disciplinary

Prisoner who had been convicted, although not yet sentenced, had no due process liberty interest in not being placed in disciplinary segregation, and therefore was not entitled to a hearing before his placement there. Tilmon v. Prator, 292 F. Supp. 2d 898 (W.D. La. 2003).

Sexual Assault

Homosexual prisoner did not successfully show that prison guard was deliberately indifferent to his safety in placing him with a cellmate who subsequently raped him. The plaintiff's statement to the guard that he was "nervous" about being placed in a cell with another prisoner was insufficient to show that the guard in fact knew of the risk and ignored it. Alleged three-day delay in providing medical treatment following the rape did not show inadequate medical care, in the absence of any showing that the delay caused any harm. Harvey v. California, No. 02-16539, 82 Fed. Appx. 544 (9th Cir. 2003).

Sexual Discrimination

New Jersey intermediate appeals court upholds Merit System Board's decision that county was entitled to designation of eight Juvenile Detention Officer positions as "male-only" on the basis of "bona fide occupational qualification" because of privacy interest of male juvenile detainees in not being viewed by female officers while showering, using toilet, and being strip-searched. In the Matter of Juvenile Detention Officer Union County, 837 A.2d 1101 (N.J. Super. A.D. 2003).

Strip Searches: Prisoners

Federal trial court certifies class action challenging county's alleged policy of conducting strip searches of all pre-arraignment jail detainees without reasonable suspicion of possession of weapons or contraband. Nilsen v. York County, 219 F.R.D. 19 (D. Me. 2003).

Telephone Access

Indiana intermediate appeals court, overturning trial court's dismissal of lawsuit, rules that trial court had jurisdiction to determined whether sheriffs and the state had the authority to enter into contracts with telephone service providers concerning charges for collect calls from inmates and to obtain profits from such charges. Argument that plaintiff prisoners and their families and attorneys had to first exhaust administrative remedies before a state utility regulatory commission rejected. Alexander v. Cottey, No. 49A02-0301-CV-32, 801 N.E.2d 651 (Ind. App. 2004).

Prisoner could not bring claims against the Department of Corrections under the Telecommunications Act of 1996, 47 U.S.C. Sec. 153, et seq., because it is not a telecommunications company or local exchange carrier. Prisoner also failed to state a claim against the Department under federal anti-trust law based on his complaint that phone charges to inmates were excessive. Bowers v. T-Netix, 837 A.2d 608 (Pa. 2003). [PDF]

Transsexual Prisoners

Prisoner suffering from gender identity disorder (GID) stated an Eighth Amendment claim for inadequate medical care based on allegation that prison officials refused to provide any evaluation of and treatment of this condition, and that state Correctional Department had a policy prohibiting any hormone or surgical treatment for inmates suffering from GID regardless of their medical condition. While the Eleventh Amendment barred claims against prison officials in their official capacities, the plaintiff prisoner stated a claim against the Commissioner of the New Hampshire Department of Corrections in his individual capacity. Barrett v. Coplan, 292 F. Supp. 2d 281 (D.N.H. 2003).

Workers' Compensation

Under state of Washington workers' compensation statute, county jail inmate trusty was entitled to medical benefits as a volunteer worker performing assigned duties without pay for injuries suffered in the course of his job. In re Wissink, # 22113-0-III, 81 P.3d 865 (Wash. App. 2003).

•Return to the Contents menu.

Report non-working links here

AELE's list of recently-noted jail and prisoner law resources.

Publication: "An Analysis of Risk Factors Contributing to the Recidivism of Sex Offenders on Probation", by John R. Hepburn and Marie L. Griffin. Prepared for the National Institute of Justice and the Maricopa County Arizona Adult Probation Department. (125 pgs., 1/2004) NCJ 203905. [PDF]

Publication: "Corrections and Law Enforcement Family Support" by Renee Edel. 147 pgs., 1/2004, NCJ 203979. A research study submitted to the National Institute of Justice concerning the nature of stress experienced by juvenile correctional officers and juvenile probation officers in Cuyahoga County Ohio, and reporting on the development of a comprehensive wellness program for Juvenile Probation and Detention Officers in an Urban Juvenile Court. [PDF].

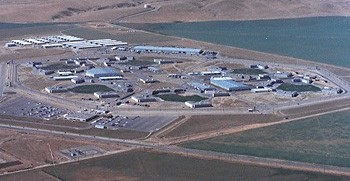

Publication: "Governments' Management of Private Prisons," by Douglas McDonald and Carl Patten. (139 pgs., 1/2004) Prepared for the National Institute of Justice. Examines state and federal governments' practices of contracting with private firms to manage prisons, including prisons owned by state and federal governments and those owned by private firms. Its focus is on contracting for imprisonment services in secure facilities, rather than for low-security or non-secure community-based facilities. The focus is also limited to facilities for convicted adult offenders, rather than facilities that serve as local jails or immigrant detention facilities. NCJ 203968. [PDF]

Publication: "Weighing the Watchmen: Evaluating the Costs and Benefits of Outsourcing Correctional Services, Part 1: Employing a Best-Value Approach to Procurement," by Geoffrey F. Segal and Adrian Moore. Reason Public Policy Institute, January 2002. (29 pgs. PDF). "Part 2: Reviewing the Literature on Cost and Quality Comparisons" by Geoffrey F. Segal and Adrian Moore. Reason Public Policy Institute, January 2002 (29 pgs. PDF).

Statistics: "Statistical Abstract of the United States 2003 Edition," U.S. Census Bureau (1030 pgs. Feb. 12. 2004). [PDF] (2001 and 2002 Editions also available online at the same location). 1995-2000 Editions. To order a print copy of the 2003 edition, click here.

Reference:

• Abbreviations of Law Reports, laws and agencies used in our publications.

• AELE's list of recently-noted jail and prisoner law resources.

Featured Cases:

First Amendment -- See also Mail

Medical Care -- See also Private Prisons

Prison Conditions: General -- See also Private Prisons

Prison Litigation Reform Act: Mental Injury -- See also Prison Conditions: General

Noted In Brief Cases:

Employment Issues -- See also Sexual Discrimination

Homosexual and Bisexual Prisoners -- See also Sexual Assault

Medical Care -- See also Medical Care: Mental Health

Medical Care -- See also Sexual Assault

Medical Care -- See also Transsexual Prisoners

Prisoner Assault: By Inmates -- See also Sexual Assault

Prisoner Transfer -- See also, First Amendment

Privacy -- See also Sexual Discrimination

Report non-working links here

Return to the Contents menu.

Return to the monthly publications menu

Access the multi-year Jail and Prisoner Law Case Digest

List of links to court websites

Report non-working links here.

© Copyright 2004 by AELE, Inc.

Contents (or partial contents) may be downloaded,

stored, printed or copied by, or shared with, employees

of

the same firm or government

entity that subscribes to

this library, but may not be sent to, or shared with others.