© Copyright 2004 by AELE, Inc.

Contents (or partial contents) may be downloaded,

stored, printed or copied by, or shared with, employees

of

the same firm or government

entity that subscribes to

this library, but may not be sent to, or shared with others.

A Civil Liability Law Publication

for officers, jails, detention centers and prisons

ISSN 0739-0998

Cite this issue as:

2004 JB Sep (web edit.)

Click here to view information on the editor of this publication.

Return to the monthly publications menu

Access the multi-year Jail & Prisoner Law Case Digest

Report non-working links here

Some links are to PDF files

Adobe Reader™

must be used to view content

False

Imprisonment

First Amendment (2 cases)

Frivolous Lawsuits

Prison and Jail Conditions: General

(2 cases)

Prison Litigation

Reform Act: Consent Decrees

Prisoner Assault: By

Inmates

Prisoner Discipline

Prisoner Restraint

Prisoner Suicide

Visitation

Access to Courts/Legal Info (2 cases)

Criminal Conduct

Defenses: Sovereign Immunity

Drugs and Drug Screening

Employment Issues

Frivolous Lawsuits

Governmental Liability: Policy/Custom

Mail

Marriage/Procreation

Medical Care (2 cases)

Prison Litigation Reform Act: Exhaustion of Remedies

Prison Litigation Reform Act: Similar State Statutes (2 cases)

Prisoner Death/Injury

Prisoner Discipline

Prisoner Suicide

Procedural: Discovery

Search and Seizure: Guards/Employees

Segregation: Administrative

Sexual Offender Programs (2 cases)

Smoking

Visitation

Five correctional employees allegedly responsible for continued incarceration of prisoner for 57 days after a court ordered him released were not entitled to qualified immunity from his federal civil rights lawsuit. A sixth employee, whose sole involvement was failing to investigate further when the prisoner returned from court without a required form, was granted qualified immunity by appeals court.

A Missouri appeals court reversed a prisoner's conviction for a theft charge, and granted him a new trial. While maintaining his innocence, he agreed to enter into a plea agreement, and was given a one-year sentence, with credit for time served. As the prisoner had then already served approximately one and one-half years, and there were no other warrants or holds on him, the judge ordered that he be immediately released.

Despite this order, county officials allegedly placed the prisoner back into county jail to await transport back to the state correctional facility he had been transported from for the court proceeding. Despite having a copy of the court's order, the prisoner remained at the county jail for four days before being transported back to the prison.

A "court return form" should have accompanied the prisoner back to the prison, along with a copy of the judge's order, but it did not. Subsequent testimony established that only 75-90% of the prisoners returning to the facility came back with a "court return form," despite explicit directions on the form requiring that it accompany the prisoner. The prisoner allegedly repeatedly protested his continued incarceration, but was "met by indifference, or admonished for refusing to accept responsibility for his crime." He was even transferred to a treatment center to complete a behavior modification program. He allegedly showed an employee there the court's order, but refused to give his only copy to her, because it was the only proof he had that he was to be released.

Despite this, the prisoner was allegedly "scolded" for his "criminal thinking" in continuing to demand release, and partially on his insistence that he be released, he claims, he was dismissed from the treatment program, and again returned to prison, where his continued demands to be released allegedly "fell on deaf ears."

He then wrote a letter to prison officials stating that he had a judge's order commanding his release, and that it had been almost two months since he should have been released. A records officer at the prison "responded" to the letter by informing him that since he was returned to the prison as a "treatment center failure," and since he "failed that program," his status was now parole violator, and he would "now be classified and transferred to your permanent institution to complete your sentence." A parole officer at the facility subsequently met with the prisoner, listened to his story, learned the truth, and arranged for his release the following day, fifty-seven days after the court had ordered him released immediately.

The prisoner filed a federal civil rights lawsuit alleging violations of his due process rights and false imprisonment under state law. Claims were asserted against the county and three county employees, as well as ten employees of the Missouri Department of Corrections, seeking compensatory and punitive damages.

The individual defendants sought summary judgment on the basis of qualified immunity. The trial court granted the motion for the county defendants, and entered judgment as a matter of law on the prisoner's claims against the county itself, finding that there was no showing that there was an official county policy or custom which caused the continued confinement or that the county employees were deliberately indifferent to the prisoner's rights.

The trial court rejected the argument, however, that the state defendants were entitled to qualified immunity, but granted summary judgment to four of them on the merits because they had no direct involvement in the allegedly unconstitutional acts in the case and the plaintiff prisoner had not alleged sufficient facts to hold them responsible in their supervisory roles. The trial court also found insufficient evidence to support the punitive damages claims against the remaining six defendants, and found that official immunity protected them against the state law false imprisonment claim.

A federal appeals court upheld the denial of qualified immunity to five of the remaining six defendants on the federal civil rights claim, ruling that the plaintiff prisoner's alleged deprivation of a recognized constitutional right which was clearly established--the right to be released when there was no justification for his continued detention, and when a court had ordered his immediate release. It found, however, that qualified immunity did shield the sixth defendant.

The defendants sought to characterize the plaintiff's claim as one alleging a constitutional violation for their "failure to investigate" his claim that he was entitled to release. The appeals court instead found that the complaint alleged "a violation of his liberty interest when he was detained for fifty-seven days after a judge ordered his release," which it found to be clearly established under current law.

Further, the prisoner possessed the order mandating his release, and there was evidence that he told a number of the defendants of its existence, and even showed it to one of them, so that no "independent investigation" was required, merely compliance with the "clear terms" of the judge's order.

The appeals court acknowledged that to prevail, the plaintiff will have to prove that the defendants were deliberately indifferent to the violation of his right. Proof of this might include evidence of the duration of his wrongful incarceration and "the nature and frequency of his protests," or the extent to which he attempted to bring the judge's order to their attention, as well as evidence that some of the defendants, in response to this knowledge, instead of making any inquiries, either ignored him or reprimanded him for his "criminal thinking."

The court granted qualified immunity to one state employee, however, whose sole involvement appeared to be failing to inquire about the prisoner's sentencing status when he returned from county custody without the requisite "court return" form. Under circumstances where a significant percentage of prisoners who go out to court are not returned with such a form, " we cannot say that a reasonable person" in this employee's shoes would know that failing to follow up on the significance of a notation "1 YR DJS" contained on the transportation list and on the whereabouts of the court return form were unlawful.

Davis v. Hall, #02-3923 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 14385 (8th Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Prison guard was not entitled to qualified immunity on the claim that he filed a false misconduct ticket against a prisoner in retaliation for his "jailhouse lawyering" activity. Law prohibiting such retaliation for exercise of First Amendment rights was clearly established.

A guard at a Michigan Department of Corrections facility appealed a trial court's decision denying him qualified immunity in a First Amendment lawsuit against him by a prisoner. The plaintiff prisoner claimed that the guard retaliated against him for his "jailhouse lawyering" activity by filing a false major misconduct ticket against him.

The incident complained of took place in July of 1995. The prisoner was required to meet with a hearing officer then on an unrelated misconduct ticket, and upon checking in with the guard to gain entry to the building, the guard allegedly said to the prisoner of his misconduct ticket, "that doesn't surprise me." When the prisoner responded that he was considering filing a grievance against the guard, the guard allegedly walked over to the prisoner and said, "You don't know who you're f ing with." He then allegedly grabbed the back of the prisoner's neck and said, "You want to f with me, b -!".

The prisoner submitted a grievance against the guard concerning the incident. The next day, the guard filed a major misconduct charge against the prisoner for "insolence," which could result in a higher security classification, placement in administrative segregation, or forfeiture of good-time credits. A hearing on the charge was "not sustained," with the hearing officer indicating that guard's credibility was "questionable," relying in part on the fact that the charge was filed "24 hours later, after the inmate had claimed to have been assaulted."

An affidavit from another inmate claimed that he overheard a conversation between the defendant guard and another guard in which the defendant described the incident and said that he did not like the plaintiff prisoner because of his repeated conflicts with him over the prisoners "jailhouse lawyer activities." The other guard allegedly recommended the writing of a false ticket against the prisoner, alleging that the guard had patted him down after a verbal threat--the version of events that would appear on the misconduct charge.

A federal appeals court ruled that the defendant guard was not entitled to qualified immunity. If the facts were as the prisoner claimed, the guard's actions would have violated the prisoner's clearly established First Amendment rights as of July 1995, according to the court.

The court rejected the argument by the guard that he was entitled to qualified immunity because the plaintiff prisoner "suffered no tangible harm" since he was found not guilty of the misconduct charge. The court found that this argument "is misguided," since the guard could not know at the time he allegedly committed the unconstitutional action, filing a false misconduct charge, that the prisoner "would be exonerated of that charge." If the guard took an unconstitutional action, the fact that it was "ultimately unsuccessful" does not make it "any less unconstitutional."

Qualified immunity should be judged based on the actions of the officer and the reasonably foreseeable consequences of those actions, not subsequent events outside of the officer's control. The injury actually suffered goes to the merits of the claim, the sufficiency of which to survive summary judgment is a settled question in this case.

Scott v. Churchill, No. 03-2427, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 15269 (6th Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet.

•Return to the Contents menu.

Federal appeals court overturns dismissal of prisoner's claim that confiscation of picture postcards from his cell might be violative of his First Amendment rights, in light of lack of evidence of the purported justification for the action. Injunction against policy preventing prisoner from receiving clippings from periodical from a correspondent upheld, but modified to clarify that the facility could still impose reasonable restrictions on the form and number of such clippings.

A Wisconsin prisoner filed a lawsuit challenging a number of actions and policies of prison officials and employees, including the confiscation of picture postcards from his cell and the application of a "publishers only" policy to prevent him from receiving, in correspondence from his father, clippings or photocopies of clippings from a publication.

The trial court dismissed the claim concerning the postcards, but issued injunctive relief to the prisoner on his claim concerning the withholding of newspaper or periodical clippings from his correspondence. It also denied his claim for damages on that claim, however, finding that the law on that issue was not clearly established, entitling the defendants to qualified immunity.

A federal appeals court found that the trial court should have allowed the prisoner's First Amendment claim on the confiscation of the postcards to proceed. The prisoner claimed that the defendants "arbitrarily" confiscated the picture postcards from his cell, telling him that he could possess no more than five postcards at one time. The prisoner did not describe the pictures on the postcard, but only stated that they "were meant to convey a message." The trial court had reasoned that, regardless of whether the prisoner had alleged a protected right to possess the postcards, the "policy" of allowing only five postcards in a cell at a time was reasonably related to security interests in limiting the number of items each inmate has in his cell.

The problem with this reasoning, the appeals court found, was that the prisoner alleged that there was nothing in the prison rule book about postcards and therefore the confiscation of his postcards was "arbitrary."

Thus, at the outset we have a disputed issue of material fact: what exactly did the prison's policy provide, and what if any exceptions did it recognize? It is impossible to evaluate the First Amendment implications of this case without the answers to those questions. We do not rule out, at this early stage, the possibility that the defendants might be able to show that Lindell's postcards were justifiably removed from his cell, but this determination cannot be made without knowing the reasons behind their removal.

Because the trial judge dismissed this claim upon screening the complaint, the defendants were never required to explain the basis for confiscating some of the postcards. The appeals court therefore ordered further proceedings on that claim.

On the issue of the "clippings," the Wisconsin Department of Corrections (DOC) was relying on a broad "publishers only" rule--a policy of allowing inmates to receive published materials only from a publisher or other commercial source. The prisoner claimed that this policy was unconstitutional to the extent that it was applied to prevent him from receiving clippings of published articles, or photocopies of such clippings. Specifically, he alleged that he was not permitted to receive a clipping of an article from Farm and Ranch Living magazine that his father sent him. The defendants argued that this denial was reasonably related to their interest in reducing the time prison staff spends looking for potential hidden messages in clippings mailed from individuals rather than publishers.

The appeals court noted that the cases upholding "publishers only" restrictions concerning the receipt of books and periodicals concerned access to entire publications, which could be used to attempt to smuggle contraband into the facility. The appeals court also noted that for the prisoner to obtain from the publisher or other commercial source a clipping such as the one his father sent him "would effectively require that he purchase the full publication."

The facility had a legitimate security interest in screening for hidden messages and a legitimate concern about the cost of staff resources used for such screening, which showed a rational connection between these interests and policy lowering the overall number of mailed items requiring screening. The appeals court found, however, that the prisoner did not have an alternative means of exercising his rights to receive the information.

The prisoner was in the facility's most restrictive housing and did not have access to the prison library's limited supply of publications. Further, subscriptions to a publication are not fully equivalent to clippings "because subscribing requires inmates to anticipate which papers might have articles that they like to read and to subscribe to all such papers." The court also reasoned that the defendants could accommodate the prisoner's rights without a large burden on staff, since they were already screening personal mail, which "could just as easily contain hidden messages."

It appears that the problem is not clippings exclusively; it is the overall volume of mail that could potentially contain hidden messages. This overall volume could be addressed by limiting the number of clippings that can be sent to an inmate. Additionally, the prison could allow only photocopies of clippings rather than the clippings themselves, so that prison staff are screening more manageable material.

The appeals court therefore found that the ban as currently applied to all clippings and copies violated the prisoners First Amendment rights.

The court found, however, that the injunction "prohibiting defendants from enforcing their publisher's only rule to the extent that it prohibits inmates from receiving any newspaper and magazine clippings and photocopies in the mail" was too broad because it could be read to prevent the prison from banning any photocopies rather than just photocopies of clippings from published sources, or from imposing reasonable restrictions on the form and number of clippings. On remand, the appeals court ordered, the trial court must modify the injunction to "make it conform more closely to the violation that was found."

Lindell v. Litscher, No. 03-2651, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 14833 (7th Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Prisoner's claim to recover damages for a sweat suit worth $25 allegedly negligently lost in federal prison laundry, brought under the Federal Tort Claims Act, was properly dismissed as frivolous. The amount of damages sought in a complaint pursued as a pauper, federal appeals court rules, is a factor which may be taken into consideration in making a determination of frivolity under the Prison Litigation Reform Act.

A prisoner at the Federal Medical Center in Butner, North Carolina, filed a lawsuit in federal court under the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA), 28 U.S.C. Sec. 2672, seeking to recover $25 from the Bureau of Prisons for the loss of his sweat suit while it was being cleaned in the institution's laundry.

The prisoner filed the lawsuit seeking to proceed as a pauper, and the trial court dismissed the claim as frivolous under the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA), 28 U.S.C. § 1915(e)(2)(B)(i), basing the decision in part by considering the minor value of the claim.

A federal appeals court upheld this result.

We hold that the amount sought in an in forma pauperis suit is a permissible factor to consider when making a frivolity determination under § 1915(e)(2)(B)(i). Further, the district court did not abuse its discretion in dismissing [the prisoner's] claim based in part on its de minimis value.

The prisoner delivered a bag of clothes to the facility's laundry for cleaning, which contained both institutional clothing and a privately owned sweat suit worth about $25. The laundry's practice was to place a tamper-proof security tie on such laundry bags as they are turned in, and to remove the tie when they are picked up. When the prisoner collected his laundry the next day, however, the bag was empty and his clothes could not be found. The prisoner claimed that the security tie fell off during washing or drying. The facility replaced his institutional clothing, but not the sweat suit.

The Bureau of Prisons denied an administrative claim, finding no negligence or wrongful conduct by any facility employee, in the absence of any evidence that the laundry staff failed to abide by its normal procedure. Additionally, it noted that at the clothing exchange area, signs on each window warned that the laundry services bears no responsibility for lost or damaged clothing.

The prisoner's lawsuit, filed after the denial of his grievance, stated that he was seeking compensatory and punitive damages of $4,000 due to the loss of his sweat suit and the alleged "malicious" denial of his administrative claim. The trial court rejected the claim for punitive damages, noting that such damages are not recoverable under the FTCA. It also found the claim for compensatory damages frivolous, citing in particular the minimal value of his suit for $25 dollars.

The appeals court rejected the argument that the absence of a stated "jurisdictional floor" or "amount in controversy" requirement in the PLRA precluded a federal trial court from considering the amount of relief requested when deciding whether to permit a prisoner litigant to proceed as a pauper, or instead to dismiss the claim as frivolous.

The word "frivolous" is inherently elastic and "not susceptible to categorical definition." It is designed to confer on district courts the power to sift out claims that Congress found not to warrant extended judicial treatment under the in forma pauperis statute. The term's capaciousness directs lower courts to conduct a flexible analysis, in light of the totality of the circumstances, of all factors bearing upon the frivolity of a claim. Just as district courts are in the "best position" to determine which claims are factually frivolous, they enjoy a comparative expertise in identifying frivolous suits generally. The overriding goal in policing in forma pauperis complaints is to ensure that the deferred payment mechanism of § 1915(b) does not subsidize suits that pre-paid administrative costs would otherwise have deterred. In implementing that goal, district courts are at liberty to consider any factors that experience teaches bear on the question of frivolity.

Whether the suit alleges significant or de minimis damages is among the many factors a district court may take into account in determining the frivolousness of a claim. Such consideration is "consistent with the goals of the in forma pauperis legislation." Nothing in the in forma pauperis statute, and nothing in 28 U.S.C. § 1915(e)(2)(B)(i) in particular, suggests that the de minimis value of a claim cannot be taken into account.

The appeals court noted that a rule that monetary value had no relevance to frivolousness would "thrust the federal judiciary deep into the minutiae of prison administration."

The appeals court rejected the argument that his claim was actually for a larger amount, since the actual value of the sweat suit was only $25.

The prisoner remained free, the court noted, to file a paid complaint with the same allegations, but "we of course express no view on the proper disposition of that case."

Nagy v. FMC Butner, No. 03-6736, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 15042 (4th Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Federal appeals court finds that Florida death row inmates' class action lawsuit claiming that high temperatures in their cells violated the Eighth Amendment prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment did not show the kind of "extreme" deprivations required for federal civil rights relief in a conditions-of-confinement lawsuit.

Death row inmates in a correctional facility in Raiford, Florida claimed that the high temperatures in their cells during the summer months amount to "cruel and unusual punishment" in violation of the Eighth Amendment. They filed a class action lawsuit seeking declaratory and injunctive relief under 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1983. After certifying the class, allowing the parties to the lawsuit to complete discovery, and viewing the unit, the trial court held a bench trial and then denied relief on the merits of the case.

A federal appeals court has upheld that result.

The facts in the case showed that the unit in which the death row prisoners were confined had neither circulating fans nor air conditioning, and that the exhaust vents on the ventilation system are not designed to cool the air. In past summers, prison officials sought to provide further relief by running the heating system without the furnace, circulating more air into the cells, and the inmates deflected this air onto themselves by attaching various items, such as the cardboard backings of legal pads, to the heater vents in the cells. For security reasons, the prison now forbids the use of these makeshift "air deflectors," and at the recommendation of the prison engineers, the guards no longer activate the heating system during the summer. The prisoners are also not allowed to have personal fans in their cells.

Evidence showed that the building remains at a relatively constant temperature, between approximately eighty degrees at night and approximately eighty-five or eighty-six degrees during the day in the summer.

Based upon the statistical data and the testimony elicited from both parties, the court ultimately concluded: According to accepted engineering standards for institutional residential settings, the temperatures and ventilation on the . . . Unit during the summer months are almost always consistent with reasonable levels of comfort and slight discomfort which are to be expected in a residential setting in Florida in a building that is not air-conditioned.

The appeals court noted that "the Constitution does not mandate comfortable prisons," and that if prison conditions are merely "restrictive and even harsh, they are part of the penalty that criminal offenders pay for their offenses against society." In general, the court stated, prison conditions rise to the level of an Eighth Amendment violation only when they "involve the wanton and unnecessary infliction of pain" or involve an "extreme" deprivation of the minimal civilized measure of life's necessities.

While the Eighth Amendment was found to apply to prisoner claims of inadequate cooling and ventilation, the appeals court further found that the conditions faced by the plaintiff prisoners, based on the evidence, did not rise to kind of extreme deprivation needed to show a violation of their rights. Mere discomfort, without more, the court noted, does not offend the Eighth Amendment. The court found it unnecessary to consider the state of mind of prison officials, i.e., whether they were deliberately indifferent to the prisoner's rights, since it found that the prisoners failed to show the kind of objective conditions which were harsh enough to state a claim.

"While no one would call the summertime temperature" at the facility "pleasant," the court stated, "the heat is not unconstitutionally excessive." The relative humidity in the building rarely rises above seventy percent, the humidity needed to support the growth of mold and mildew, and the cells are not exposed to direct sunlight. Additionally, every cell has a sink with hot and cold running water, every inmate has a drinking cup, and the prisoners are "generally sedentary," and are not compelled to perform prison labor. Additionally, they have some limited opportunities to gain relief in air-conditioned areas, such as visiting areas, the library, etc.

We are sensitive to the inmates' plight, and we recognize that "constitutional rights don't come and go with the weather." But "extreme deprivations are required to make out a conditions-of-confinement claim" under the Eighth Amendment." Under the standards we apply, we cannot say that the prisoners at the Unit have cleared this high bar.

Chandler v. Crosby, No. 03-12017, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 16246 (11th Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

•••• Editor's Case Alert ••••

Prison's policy of constant illumination of cell in administrative segregation unit was reasonably related to a legitimate interest in guard security, so that prisoner could not pursue his claim that it violated his rights under the Eighth Amendment because it deprived him of sleep.

A Texas prisoner confined to an administrative segregation unit reserved for the most dangerous prisoners, and who has been there since April of 2000, alleged that bright fluorescent lights and light bulbs completely illuminate his cell twenty-four hours a day. In a federal civil rights lawsuit, he asserted that he cannot sleep because of these lights, and that his grievances over this were rejected with an explanation that it was necessary to keep the lights on for security reasons.

Prison officials also rejected a suggestion that the lights could be dimmed during the night and turned up by guards when they passed by to inspect the cells, arguing that such a practice would be even more disruptive of sleep.

The trial court dismissed the lawsuit as frivolous and for failure to state a claim under 28 U.S.C. Sec. 1915A. It found that the policy was a reasonable security measure, and that, although sleep is a basic human need, the prisoner had not shown a deprivation rising to the level of an Eighth Amendment violation. There was no evidence, the court noted, that the prisoner had complained to medical personnel about lack of sleep.

In upholding this result, a federal appeals court found that, even assuming for the purposes of argument, the prisoner could allege conditions leading to a sleep deprivation sufficiently serious, he could not establish an Eighth Amendment violation because he could not show that the deprivation is "unnecessary and wanton." The court found the policy justified and reasonably related to the legitimate penological interest of guard security.

One judge, in concurring with the result, said that he regarded the judicial attention paid to the prisoner's claim as "much ado about nothing," since "a little cloth over his eyes would solve the problem, negate deprivation, and escape this exercise in frivolity." A strong dissent was filed in the case by the Chief Judge of the Fifth Circuit, who stated that he would hold that the court abused its discretion in dismissing the claim as frivolous.

Chavarria v. Stacks, No. 03-40977, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 14945 (5th Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Federal appeals court rejects challenges to consent decree requiring improvements to Puerto Rican prison conditions, including claim that the court's order violated the requirements of the Prison Litigation Reform Act. Court declines to order termination of consent decree requiring privatization of inmate health care, pointing to continuing serious problems.

Correctional officials in Puerto Rico attempted to challenge a consent decree entered in 1998 requiring improvements in their prison system, including the proposed privatization of medical and mental health care throughout the correctional system. The officials argued that the court acted outside its authority in entering the consent degree, that the order was void for failure to meet the requirements of section 802 of the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA), 18 U.S.C. § 3626, and that the order should be terminated because the trial court's supportive fact-finding was "clearly erroneous" and "infected by errors of law."

A federal appeals court has rejected each of these arguments, and upheld the trial court's refusal to vacate or modify the consent decree. The lawsuit in question was filed in the 1970s as a class action by Puerto Rican inmates, and the trial court appointed a monitor for the Puerto Rican prison system. Various changes to the medical and mental health care provided there were ordered over the years, along with multi-million dollar fines for alleged failure to comply with the court's orders.

In 1997, the parties filed a stipulation with the court embodying a consensus that a private non-profit corporation should be formed to provide medical and mental health services to the inmate population. The trial court endorsed this plan, and an entity was formed, but a "monetary infusion," including roughly $55 million in accrued fines, made available by the trial court "has not yet brought the project to fruition." The entity has, to date, developed an administrative infrastructure, fashioned some programs, and "constructed needed facilities," and is in the process of developing a new acute care hospital, but the project is not at the point where it was intended to be at this time, according to the court, and has not yet treated a single patient!

Correctional officials, emphasizing this "protracted period of delay and the mounting costs of completing the necessary infrastructure," filed a motion under the PLRA to terminate the privatization component of the existing consent decree. The trial court rejected this.

The appeals court found that the trial court had equitable powers to enter the original consent decree order, and that, in addition, the predecessor to the current Secretary of the correctional department stipulated to the privatization remedy and had the authority to do so.

The appeals court also found that the consent decree and the trial court's rejection of attempts to terminate or modify it complied with the requirements of the PLRA. Injunctive relief "shall not terminate if the court makes written findings based on the record" that the relief is still required.

The appeals court found that the evidence in the record showed that health care for inmates in Puerto Rican prisons "remains constitutionally deficient," and that the denial of medical and mental health services is "massive and systematic." Examples included:

* In 2003, one-fourth of all inmates who requested sick call did not get it;

* only 55% of all ambulatory care appointments actually took place;

* only 49% of specialist consultations deemed necessary for serious conditions were arranged;

* "as a rule," medically prescribed diets for inmates were habitually ignored;

* only 31.3% of inmates who had been diagnosed HIV-positive were receiving treatment; and

* inmate mortality rates were rising.

The court characterized these examples as "but the tip of a particularly unattractive iceberg." While correctional officials presented testimony by experts as to the purported adequacy of its health care, the appeals court found that the trial court could properly disregard this testimony as lacking in credibility. While "some noteworthy advances" had been made in the delivery of health care to inmates, there were still "substantial deficiencies" in "virtually every aspect of the inmate health care system," justifying a comprehensive injunctive decree.

The appeals court also found that the order in question was sufficiently narrow and only went as far as required to remedy the actually existing problems. It also rejected the argument that there were sufficient problems with the way the evidentiary hearing was held on the issue of terminating the decree to make its findings insupportable.

Feliciano v. Rullan, No. 04-1300, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 16258 (1st Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet.

•Return to the Contents menu.

•••• Editor's Case Alert ••••

Prisoner was properly awarded $820,000 in damages against county for failure to protect him from physical assault by another inmate who he had helped imprison by cooperating in law enforcement narcotics investigation. Federal appeals court rejects argument that damages were excessive, and upholds trial court's reduction of jury's prior award of $1,610,000.

An inmate at the Nassau County Correction Center in New York had previously cooperated with law enforcement in the investigation of an individual by participating in a controlled purchase of narcotics from him. After that person was arrested, it was recorded in the county's computer system that the two prisoners should not be housed in the same dormitory. The prison official in charge of housing assignments at the facility, however, failed to notice that instruction, and the two prisoners were subsequently placed in the same dormitory.

A day later, the informant inmate was allegedly severely beaten by the man he had informed on, receiving head injuries that left him in a coma for six days, necessitated surgery, and caused subsequent seizures and other ill effects. The injured informant prisoner sued the county for both violation of civil rights and state law negligence in failing to protect him from the assault. His spouse also asserted a state law claim for loss of consortium.

At the conclusion of the trial, the judge dismissed the federal civil rights claim for lack of sufficient evidence, and the jury returned a verdict in favor of the plaintiff prisoner of $300,000 for past pain and suffering, and $1,250,000 for future pain and suffering, as well as awarding his wife $60,000 for loss of consortium, for a total award of $1,610,000. The award for future pain and suffering included damages for the "residual fear of living with the possibility of having seizures, and the possibility of future seizures, coupled with headaches and depression."

The trial judge rejected challenges to the $300,000 past damages award as excessive, but found that a more appropriate award for future pain and suffering was $500,000, rather than the $1,250,000 awarded by the jury. It also ordered the loss of consortium award reduced from $60,000 to $20,000.

The county appealed, arguing that the damages awarded were still excessive, and the plaintiffs appealed, arguing that the trial court abused its discretion in granting a new trial unless they agreed to reductions in the amounts awarded by the jury for future pain and suffering and loss of consortium.

A federal appeals court ruled that the plaintiffs, in agreeing to accept the reduced awards, lost the right to challenge it on appeal.

The appeals court found nothing excessive about the award of compensatory damages for past injuries, in light of the fact that the prisoner had to undergo emergency brain surgery as a result of the assault, and suffered a cerebral concussion, post-concussion syndrome, depression, a seizure disorder, and cerebral encephalopathy.

It also found the $500,000 reduced award for future pain and suffering appropriate, since the prisoner's injuries caused him continuing leg and back pain, headaches, a long scar on his head and face which allegedly remained sore three years after the incident, and the prisoner had a problem with auditory hallucinations and potential sexual difficulties, as well as the fear of future seizures. These injuries to the prisoner also amply justified the $20,000 loss of consortium claim by his wife.

Rangolan v. County of Nassau, #03-7367, 370 F.3d 239 (2nd Cir. 2004).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Trial court properly denied correctional employees qualified immunity on prisoner's due process claims that he was not provided with proper notice of the charges and the evidence relied on in connection with his prison disciplinary hearing, but should have granted them qualified immunity on prisoner's claim that evidence presented was insufficient to support a finding of guilt.

A New York prisoner claimed that he was denied due process in connection with a disciplinary action taken against him. Specifically, he claims that he was not provided adequate notice of the charges against him, that correctional officials engaged in non-disclosure of the evidence relied on, and that the evidence submitted at the hearing was insufficient to support a finding of his guilt. The defendant correctional employees appealed the trial court's denial of qualified immunity on the prisoner's due process claims.

A federal appeals court ruled that the defendants were entitled to qualified immunity on the prisoner's claim that the evidence presented was insufficient to support a finding of guilt. While the prisoner presented a "viable due process claim" on that issue, the defendants could reasonably have thought, the court found, that their "conduct conformed to established law with respect to assessing the reliability of evidence supplied by confidential informants." It upheld, however, the denial of qualified immunity on the due process claims concerning the prisoner's alleged lack of adequate notice of the charges and evidence relied on in the charges against him.

The prisoner was charges with violations of prison rules providing that "Inmates shall not, under any circumstances make any threat, spoken, in writing, or by gesture" and that "Inmates shall not lead, organize, participate, or urge other inmates to participate, in work-stoppages, sit-ins, lock-ins, or other actions which may be detrimental to the order of facility."

The prisoner was allegedly identified through confidential sources as having urged and organized other inmates to participate in a planned inmate demonstration at the facility, including a work/program stoppage on January 1, 2000, referred to as the "Y2K strike." Prison officials sought to avert the strike by ordering a lockdown, but once the lockdown ended on January 6, 2000, the strike occurred anyway.

The prisoner argued that the misbehavior report did not provide him with adequate notice of the conduct at issue since it did not identify any person whom he had threatened or organized, did not indicate where in the prison the alleged misconduct had occurred, and failed to clearly indicate the date of his alleged misconduct. He also denied urging or threatening anyone to participate in the strike.

The hearing officer ruled that the report provided sufficient detail, and that he would call the complaining officer to testify in support of the charges and to answer the questions the prisoner posed. He also stated that he would hear evidence outside of the prisoner's presence to make a personal assessment of the credibility of the confidential sources whose information supported the disciplinary charges.

The officer later testified that it had been learned from various confidential sources that the prisoner had assumed leadership of a group of Dominican inmates, that he was the "Captain" of "C Block," and that he had tried to enforce participation in the strike by threatening inmates. These threats were not, the officer stated, against any particular person, but were "open threats" against any one who would go against the strike. The date on the report, she clarified, alluded to the date and time she filed the report, not the date and time of any misconduct. The hearing officer concluded that the report's reference to January 1, 2000 as the planned strike date gave sufficient notice of the approximate date and time of the alleged misconduct and that the report's identification of the prison as the site of the misconduct was adequate.

The hearing officer heard testimony out of the prisoner's presence from three officers concerning information received from five confidential informants who implicated the prisoner in the strike. The officers stated that the informants would not agree to testify at the hearing because they feared reprisals.

When the hearing reconvened with the prisoner present, the hearing officer rejected the argument that the prisoner had the right to know the substance of the confidential information revealed in the closed session. The prisoner was found guilty of organizing inmates to participate in the strike, but not guilty of making threats.

"The notice required by due process is no empty formality," the court stated, but is required so that the charged inmate can prepare a defense and not be made to explain away "vague charges."

Toward this end, due process requires more than a conclusory charge; an inmate must receive notice of at least some "specific facts" underlying the accusation. Such notice is especially important where, as in this case, large parts of the disciplinary hearing are conducted outside the inmate's presence.

In this case, the notice provided was "devoid of specific facts," describing no words, actions, or means employed by the prisoner to further the strike, identifying no inmates toward whom the alleged misconduct was directed, and identifying no specific locations in the prison where the conduct took place. Additionally, the date and time listed did not reflect the date and time of the alleged misconduct. The appeals court found this to be inadequate notice.

Even at the hearing, the prisoner was not informed of specific facts as to what he was alleged to have said and done or when, and none of the specifics of the information provided by the confidential informants were revealed to him, supporting his claim of inadequate disclosure of the evidence against him. There was no indication that the disclosure of this substance of the information, as opposed to the identity of the informants, would pose a threat to the informants' safety.

Finally, on the issue of whether the evidence supplied by the confidential informants and their statements was sufficient to support the conviction against the prisoner, the court noted that much of what was presented was not based on their personal knowledge but on communications from third parties.

We agree that when confidential information presented at a prison disciplinary proceeding involves multiple levels of hearsay, a hearing officer cannot determine the reliability of that information simply by reference to the informant's past record for credibility. Credible informants may, after all, unwittingly pass along suspect information from unreliable sources. For this reason, the officer must consider the totality of the circumstances to determine if the hearsay information is, in fact, reliable.

In this case, where the prisoner appeared to have been deprived of both adequate notice and the substance of the evidence against him, the hearing officer's failure to probe and "assess the totality of the circumstances in assessing the reliability of third-party hearsay information disclosed by confidential informants makes it impossible for us to conclude as a matter of law at this stage of the case" that the prisoner could not present a viable claim as to the sufficiency of the evidence.

Despite this, however, the appeals court found that the hearing officer was entitled to qualified immunity on the sufficiency of the evidence issue, since the courts have not, it stated, clearly defined standards for determining what constitutes "some evidence" sufficient to support a finding of guilt in prison disciplinary hearings. In particular, the court found, the law in the Second Circuit was not clear, at the time of the hearing at issue, as to whether "a hearing officer was required to conduct an independent assessment or whether he could rely on the opinion of another person." The court stated that it had attempted to clarify that in this decision by emphasizing that "due process requires an independent assessment of the confidential informant's credibility."

We today hold that the reliability of evidence is always properly assessed by reference to the totality of the circumstances and that an informant's record for reliability cannot, by itself, establish the reliability of bald conclusions or third-party hearsay. Because this principle was not clearly established before today, it was objectively reasonable for defendants to think that an independent assessment of the credibility of the confidential informants who proffered evidence against [the prisoner], satisfied due process, and that [the hearing officer] could, without further inquiry, rely on the third-party hearsay disclosed by those informants as some reliable evidence of [the prisoner's] participation in the Y2K strike.

The hearing officer was there entitled to qualified immunity on the sufficiency of the evidence claim.

Sira v. Morton, No. 03-0156, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 15897 (2d Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Prisoner was properly awarded $1,500 in compensatory damages for allegedly being left in restraint chair for long periods of time, and $500 for alleged excessive use of force against him, but trial court properly did not award punitive damages in light of fact that the prisoner admitted disobeying orders, and that the facility had not developed policies governing the use of the restraint chair.

An Arkansas inmate sued seeking damages for injuries he allegedly suffered during his first six days of incarceration at a county jail. He claimed that he received unprovoked beatings from guards and was placed in a "torture chair" for long periods of time. The trial court found in favor of the prisoner and against a captain for $1,500 in compensatory damages on the restraint-chair claim, and in favor of the prisoner and against one deputy for $500 in compensatory damages on the excessive-force claim. It found in favor of all other defendants.

The prisoner appealed, arguing that the trial judge should have found all the named correctional employees liable, and also should have awarded him punitive damages.

A federal appeals court upheld the trial court's decisions in their entirety. It rejected the plaintiff's argument that the trial court had abused its discretion in refusing to allow him to call additional witnesses and in failing to grant his request for a medical examination. The appeals court noted that the plaintiff did not state what further testimony the requested witnesses would have provided, and many of them had no knowledge of the incidents about which the plaintiff complained. The physical examination was unwarranted, the court found, since the court "credited the testimony" of the plaintiff and the inmate witnesses as to the injuries he received, and his hospital and medical records for the relevant period were entered as exhibits.

The court found that the trial court had sufficient evidence to find the two defendants liable, which it did, but that there was insufficient evidence presented to find anyone else liable for the incidents.

The trial court also did not abuse its discretion in concluding that the prisoner was not entitled to punitive damages. In the excessive force incidents with the deputy, the prisoner admitted disobeying orders and resisting the deputy, and the evidence also supported a finding that the prisoner was left for prolonged periods in the restraint chair on three occasions because "specific policies regarding the chair's use had not been developed." To award punitive damages, the court noted, there must be a showing that the conduct was motivated by "evil motive or intent," or involved reckless or callous indifference to federally protected rights.

Guerra v. Drake, #03-3137, 371 F.3d 404 (8th Cir. 2004).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Federal appeals court reinstates claim against county sheriff for failing to protect detainee against risk of suicide after he learned that he had just made a suicide attempt at another jail from which he had been transferred. Sheriff allegedly failed to inquire into the details of this prior attempt and placed the prisoner in a cell with a bedsheet with which the prisoner successfully killed himself. The prior suicide attempt days before had also involved the use of a bedsheet.

A man arrested on an outstanding warrant became violent and threatening when brought to the county jail. Due to this behavior, the sheriff decided to transfer him to a jail in another county. Once there, he allegedly informed of the officers that he "was going to hang it up." Officers shortly after this found the prisoner in his cell with a bed sheet tied around the neck, and attempting to fight them off when they tried to help him. They sprayed him with pepper spray and placed him on a suicide watch for the remainder of his stay there. He was then transferred back to the original county jail to attend a hearing in his criminal case.

His attorney had reached a plea agreement under which he would serve 15 years for his offenses. The prisoner allegedly did not want to return to prison, as it was widely known that he had provided information about a prison killing, and he faced possible retaliation if he were to go back. After court, a deputy sheriff picked him up for the trip back to the original county jail. This deputy was informed about the prior suicide attempt.

On the drive back to jail, the prisoner allegedly said something like if he received more than a 15-year sentence he would "die and take someone with him." The prisoner was placed in a cell by himself, but an intake form, which asks about prior suicide attempts, was not filled out. An employee at the jail was told that she should "keep an eye" on the prisoner and perform ten-minute checks on him, but she was allegedly not told about the prior suicide attempt.

The prisoner was later found hanging from the cell bars with a bed sheet tied around his neck. Attempts to revive him were unsuccessful and he died. His estate sued the sheriff, a chief deputy, the jail employee, and the county for alleged deliberate indifference to the risk of the prisoner successfully attempting suicide. The trial court granted summary judgment on the basis of qualified immunity to the individual defendants and also ruled that the plaintiff had failed to show that the county had notice that its training was allegedly inadequate.

Reversing on the claims against the defendant sheriff, the federal appeals court noted that the sheriff was allegedly told, when the prisoner was returned to his custody, that the prisoner had attempted suicide in the other county's jail, but failed to follow up with the other county to find out the details. Had he done so, he would have found out that the prisoner used a bedsheet to try to kill himself. Instead, he brought the prisoner to a cell which was double-locked behind two sets of doors, contained a bed sheet and exposed ceiling bars, and ordered that he be left there alone.

Under these circumstances, there was a genuine issue as to whether the sheriff was deliberately indifferent to a serious risk that the prisoner would commit suicide.

The appeals court upheld the trial court's decision as to the other individual defendants and the county.

Turney v. Waterbury, No. 03-2375, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 14811 (8th Cir).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

•••• Editor's Case Alert ••••

Correctional policy denying a sex-offender contact visits with minors, including family members, did not violate his First Amendment right to freedom of association, and was rationally related to legitimate interests in promoting institutional security and the safety of children.

A convicted sex-offender incarcerated in a Pennsylvania correctional facility filed a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of a Department of Corrections Policy, DC-ADM 812 [PDF], entitled "Inmate Visiting Privileges." Specifically, he objected to a portion of the policy under which officials refused to permit contact visits between him and minor children because of his sex-offender status. The plaintiff prisoner is permitted only non-contact visits with minors, including his sister and children of friends.

The non-contact visits take place in an area where the visitor and the inmate are separated by a glass screen and conversations take place via telephone. The prisoner claimed that this violated his First Amendment right to intimate family association, and that the safety of minors within the prison visitation setting may be assured by other means. He argued that the policy was an "exaggerated response to prison concerns," and that the Department had limited his visitation rights in retaliation for his refusal to participate in sex-offender treatment programs." The prisoner asserted that he was discharged from a therapeutic program for sex-offenders because he refused to abandon religious beliefs that were violated by certain philosophies of the program.

The prisoner also argued that the policy was wrong because the Department does not stand in the position of a parent over the visiting minors, and that the efforts of prison officials "to protect children against the wishes of their very own parents" demonstrated "flawed logic, and even shows discrimination against some visitors."

The court rejected all these arguments, finding that the prisoner was not entitled to an injunction against the enforcement of the policy. It ruled that the regulations limiting the visitation rights of sex-offenders are "rationally related to legitimate, and obvious, penological interests" of promoting security and protecting children. The court pointed to the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Overton v. Bazzetta, 539 U.S. 126 (2003), in which the Court upheld prison regulations restricting the visitation rights of inmates classified as the highest security risks, including allowing them only non-contact visitation and only allowing visits from children who were accompanied by adults.

While it is true that there is constitutional protection for certain types of personal relationships, including association among members of an immediate family, including children and grandchildren, "many of the liberties and privileges enjoyed by other citizens must be surrendered by the prisoner" and an inmate "does not retain rights inconsistent with proper incarceration," so that "some curtailment" of the freedom of association "must be expected in the prison context."

Garber v. Pennsylvania Department of Corrections Secretary, 851 A.2d 222 (Pa. Cmwlth. 2004).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Report non-working links here

Access to Courts/Legal Info

Trial court abused its discretion when it first denied a plaintiff prisoner's motion to testify by deposition and then dismissed his lawsuit for want of prosecution based on the prisoner's failure to be present in court. The prisoner had also filed the appropriate motions to be allowed to come to the trial or in the alternative to have the trial at the prison, so that the judge's actions denied him equal access to the courts. McConico v. Culliver, #2020744, 872 So. 2d 872 (Ala. Civ. App. 2003).

Federal appeals court rejects prisoner's claim that he was forced, during a modified lockdown following a prison riot, to choose between his constitutional right to regular outdoor exercise and his constitutional right of access to the courts. Evidence showed that, during the period in question, he had participated in between two to six hours of outdoor exercise per week, as well as managing to use the law library for a period of time sufficient to amend his complaint in one lawsuit, and to successfully file the lawsuit making the immediate claim. This showed that neither right was actually denied. Knight v. Castellaw, No. 03-16870, 99 Fed. Appx. 790 (9th Cir. 2004).

Criminal Conduct

Federal appeals court upholds enhanced 46-month sentence imposed on correctional officer who pled guilty to conspiracy to violate the civil rights of jail detainees he was supervising, based on unusual vulnerability of prisoner with Tourette's syndrome to assault. The officer failed to show reversible error in the trial court's finding that he had knowledge of the prisoner's unusual vulnerability of Tourette's syndrome, and the trial court noted that, prior to the alleged beating of the prisoner, either the defendant or another officer was heard yelling, "we'll beat the Tourette's out of you." United States v. Donnelly, #03-2022, 370 F.3d 87 (1st Cir. 2004).

Defenses: Sovereign Immunity

State of Texas was entitled to sovereign immunity against prisoner's claim for personal injury resulting from contact with a razor-wire fence surrounding a prison recreation yard. The presence of the razor wire there did not constitute either an "ordinary premises defect," or a "special defect" enumerated as an exception to sovereign immunity in the state's Tort Claims Act, V.T.C.A., Civil Practice & Remedies Code, Sec. 101.022. Retzlaff v. Texas Department of Criminal Justice, No. 01-02-00437-CV, 135 S.W.3d 731 (Tex. App. 1st Dist. 2003), rehearing denied March 4, 2004.

Drugs and Drug Screening

New York inmate was properly found guilty of violating prison rules against unauthorized use of drugs, based on substantial evidence, including positive urinalysis test and supporting documentation. Prisoner was also properly found guilty of sexual misconduct based on testimony of correctional officer who witnessed the inmate's wife in the prison visiting room with her hand down inside the inmate's pants. Sanchez v. Selsky, 778 N.Y.S.2d 561 (A.D. 3d Dept. 2004). [PDF]

Employment Issues

State correctional officers were not entitled to a preliminary injunction against discipline of them for associating with Outlaws Motorcycle Club, a group alleged to be a criminal gang. The directive prohibiting officers from conduct constituting or giving rise to the appearance of conflict of interest, engaging in unprofessional or illegal behavior that could reflect negatively on the Department, and acting in ways jeopardizing institutional security or the health, safety, or welfare of the staff or inmates, which was the basis for the discipline, was not overbroad under the First Amendment. Piscottano v. Murphy, 317 F. Supp. 2d 97 (D. Conn. 2004).

Frivolous Lawsuits

Prisoner's lawsuit against corrections officers was properly dismissed as frivolous. Prisoner was found to be a "vexatious litigant," and failed to provide the required information in an affidavit to the court concerning his past 22 lawsuits and detailing the facts for which relief was sought in those past lawsuits. Carson v. Walker, No. 07-01-0402-CV, 134 S.W.2d 300 (Tex. App. 2003).

Governmental Liability: Policy/Custom

Inmate in New York correctional facility could not pursue federal civil rights lawsuit against county, county prosecutor, or county sheriff claiming that they violated his constitutional rights because they failed to prosecute correctional officers for allegedly threatening him on three occasions, in the absence of any allegation that the failure to prosecute was the result of any official policy or custom. Additionally, neither prosecutor nor sheriff were in a supervisory position within the prison hierarchy, and therefore did not have a duty to protect him from these alleged threats. Lewis v. Gallivan, 315 F. Supp. 2d 313 (W.D.N.Y. 2004).

New York prisoner's claim that correctional employees deliberated tampered with his mail, including both incoming and outgoing legal, personal, and political mail, without cause or justification, adequately asserted a claim for violation of his First Amendment rights. Nash v. McGinnis, 315 F. Supp. 2d 318 (W.D.N.Y. 2004).

Marriage/Procreation

While a prisoner had a fundamental constitutional right to marry, there was no duty on the part of a court clerk to travel to the prison to conduct a required oral examination to enable the prisoner to obtain a marriage license without personally appearing at the clerk's office, or to implement video conferencing so that the interview could be remotely conducted. In re Appeal of Coats, 849 A.2d 254 (Pa. Super. 2004). [PDF]

Medical Care

Florida Department of Health illegally repealed provisions of the state administrative code governing health and safety conditions in state correctional facilities by failing to comply with rule-making requirement that it identify the statute implemented by the repeal. Court also rejects Department's argument that state statutes imposed a duty on it to regulate conditions only in mental institutions, finding that it also has a duty to regulate prison conditions. Osterback v. Agwunobi, No. 1D03-1589, 873 So. 2d 437 (Fla. App. 1st Dist., 2004). [PDF]

A correctional facility in Connecticut is not an "other facility" which is subject to the requirements of a "patient's bill of rights" under state law, C.G.S.A. Sec. 17a-540(a). Accordingly, the rights given to patients under that statute to assist with the planning for their discharge from a hospital for psychiatric disorders do not apply when the patient being discharged is a convicted felon and is subject to a further period of incarceration. The estate of an inmate who died in a correctional facility could not, therefore, rely on alleged violations of the patient's bill of rights in seeking damages from the facility and its employees for failure to provide adequate and proper medical care, mediation, and supervision of the prisoner. Wiseman v. Armstrong, No. 16988, 850 A.2d 114 (Conn. 2004). [PDF]

Prison Litigation Reform Act: Exhaustion of Remedies

California prisoner's lawsuit claiming that corrections officers assaulted him dismissed for failure to totally exhaust available administrative remedies as required by the Prison Litigation Reform Act, 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1997e(a). Entire complaint dismissed when it contained a mixture of both exhausted and unexhausted claims, although prisoner could, if he wanted, file a new complaint concerning only claims on which he had exhausted administrative remedies. Mubarak v. California Department of Corrections, 315 F. Supp. 2d 1057 (S.D. Cal. 2004).

Prison Litigation Reform Act: Similar State Statutes

A provision in the Wisconsin state Prison Litigation Reform Act, W.S.A. 814.25(2), which prohibits the award of costs against the state in lawsuits brought by inmates was not a violation of equal protection. State government could rationally decide that inmates who were prevailing plaintiffs should not be reimbursed for their costs from public funds since public funds already provide them with law libraries, paper, and pens to use to draft legal documents in lawsuits. State Ex Rel. Harr v. Berge, No. 03-2611, 681 N.W.2d 282 (Wis. App. 2004). [PDF]

For purposes of a requirement, in a Texas state Inmate Litigation Act, V.T.C.A. Civil Practice & Remedies Code Secs. 14.002(a) and 14.005(a, b), that a prisoner filed a civil lawsuit within 31 days after he exhausts available administrative remedies on a grievance, a prisoner's lawsuit is deemed to have been filed at the time that prison authorities receive the document for mailing, so long as it is properly addressed and stamped. Warner v. Glass, No. 03-0214, 135 S.W.3d 681 (Tex. 2004). [PDF]

Prisoner Death/Injury

Ohio prisoner failed to prove that failure to grant his request for a bottom bunk assignment was the cause of the injuries he suffered when he fell and struck his head while attempting to climb into his top bunch, and therefore was not entitled to damages. Medical personnel at the facility had no indication that the prisoner had a need for a bottom bunk assignment because of a prior foot injury. Bell v. Ohio Dept. of Rehabilitation and Correct., No. 2002-06391-AD, 810 N.E.2d 467 (Ohio Ct. Cl. 2004). [Also see docket in the case].

Prisoner Discipline

Prisoner who "laughed and clapped" while watching terrorist attacks on television on 9-11-2001, and then told another inmate that he saw their "chance to take this place," was properly found guilty of violating a prison disciplinary rule prohibiting rioting. Linares v. Goord, 778 N.Y.S.2d 550 (A.D. 3d Dept. 2004). [PDF]

Prisoner Suicide

Prison psychiatrist and mental health worker did not act with deliberate indifference in returning prisoner, formerly found to be suicidal, to the general prison population, after which he successfully killed himself. The prisoner, at the time, appeared to have responded positively to the medication provided, and signed a contract in which he agreed not to hurt himself or others. The court finds that there was nothing from which the defendants could have inferred a strong likelihood that he would commit suicide at that time. Soles v. Ingham County, 316 F. Supp. 2d 536 (W.D. Mich. 2004).

Procedural: Discovery

In a lawsuit by a New York prisoner seeking damages for injuries he suffered while operating router equipment in a prison work assignment, the court ruled that the "drastic remedy" of striking the State's answer to the prisoner's complaint was not justified by the State's failure to produce, in discovery, its accident report and the maintenance records for the router, but found that this was sufficient to support an inference that, if these records had been produced, they would have been unfavorable to the State. Gentle v. State of New York, No. 96927, 778 N.Y.S.2d 660 (Ct. Cl. 2004).

Search and Seizure: Guards/Employees

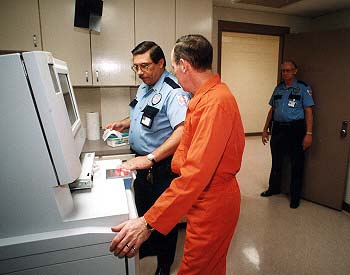

Federal court upholds county jail employee search policy including random pat-down searches by same sex employees of "all areas" of the searched employee's body, including their abdomen and groin, and removal of outer clothing, belts, and shoes. Search policy was justified by a strong interest in preventing the introduction of contraband into the facility and by employee's diminished expectation of privacy on the job. Court also notes that the policy was applied uniformly to every employee and also to visitors at the facility who have contact visits with prisoners. Allegheny County Prison Employees Independent Union v. County of Allegheny, 315 F. Supp. 2d 728 (W.D.Pa. 2004).

Segregation: Administrative

Prison officials were entitled to qualified immunity from inmate's claim that they violated his due process rights in deciding to keep him in administrative segregation. The record in the case showed that the prisoner was given an opportunity to present information to the committee which made the decision, and the committee regularly reviewed the prisoner's confinement every seven days during the first two months, and once a month after that. Torres v. Irvin, No. 02-0295, 99 Fed. Appx. 292 (2nd Cir. 2004).

Sexual Offender Programs

Prisoner's loss of certain incentive privileges because he was removed from a sexual abuse treatment program did not violate any recognized liberty or due process right. Laubach v. Roberts, No. 91, 329, 90 P.3d 961 (Kan. App. 2004).

Prisoner's Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination was violated by sexual offender counseling program's requirement that he reveal his history of sexual conduct, including actions for which criminal charges could still be brought, or else lose good time credits. Defendant prison officials, however, were entitled to qualified immunity, as the law on the issue was not clearly established. Donhauser v. Goord, 314 F. Supp. 2d 119 (N.D.N.Y. 2004).

Smoking

Prison officials involved in refusing to agree to prisoner's request that he be assigned to a non-smoking cell were not entitled to qualified immunity from his claim that this subjected him to a risk of serious damage to his future health, as well as present aggravation of respiratory problems. The prisoner's right, under these circumstances, not to be subjected to these risks was clearly established, and there was evidence that the prisoner was confined nineteen hours a day in a small, enclosed cell with a habitual smoker of cigars. Johnson v. Pearson, 316 F. Supp. 2d 307 (E.D. Va. 2004).

Visitation

Prisoner properly denied further visitation of inmate's fiancee to prison based on evidence that he sent money to her in exchange for heroin she allegedly conspired to bring into the facility. Correctional officials had reasonable grounds to believe that continued visits would have caused a serious threat to prison security. Substantial evidence also supported determination that prisoner was guilty of violating disciplinary rules against possession of money, promoting prison contraband, and smuggling. Encarnacion v. Goord, 778 N.Y.S.2d 562 (A.D. 3d Dept. 2004). [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Report non-working links here

AELE's list of recently-noted jail and prisoner law resources.

Employment Discrimination: Federal Equal Employment Opportunity Statistical Reports of Discrimination Complaints Bureau of Prisons (BOP) 2004 - PDF, HTML.

Prison Rape: Data Collections for the Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003 The Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003 (Public Law 108-79, signed on September 4, 2003), requires the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) to measure the incidence and prevalence of sexual assault within the Nation's correctional facilities. This Status Report includes highlights of the legislation and addresses some of the complexities of collecting sensitive data from various correctional populations. The report also contains descriptions of new data collection efforts that BJS is undertaking in order to meet the requirements of the legislation. 07/04 NCJ 206109 Acrobat file (26K) | ASCII file (651K) Draft survey instruments for the Survey on Sexual Violence: State Prison Systems SSV2 (568K) Local Jail Jurisdictions SSV3 (568K) State Juvenile Systems SSV5 (576K)

Statistics: Probation and Parole in the United States, 2003 Reports the number of persons on probation and parole, by State, at year end 2003 and compares the totals with year end 1995 and 2002. It lists the States with the largest and smallest parole and probation populations and the largest and smallest rates of community supervision, and identifies the States with the largest increases. The Bulletin also describes the race and gender of these populations and reports the percentages of parolees and probationers completing community supervision successfully, or failing because of a rule violation or a new offense. Highlights include the following: The adult probation population grew 1.2% in 2003, an increase of 49,920 probationers, less than half the average annual growth of 2.9% since 1995. Overall, the Nation's parole population grew by 23,654 in 2003, or 3.1%, almost double the average annual growth of 1.7% since 1995. 49% of all probationers had been convicted of a felony, 49% of a misdemeanor, and 2% of other infractions. The total Federal, State, and local adult correctional population -- incarcerated or in the community -- grew by 130,700 during 2003 to reach a new high of nearly 6.9 million. 07/25/04 NCJ 205336 Press release | Acrobat file (337K) | ASCII file (34K) | Spreadsheets (zip format 60K)

Statistics: Profile of Jail Inmates, 2002 Presents findings from the Survey of Inmates in Local Jails, 2002, the only national source of detailed information on persons held in local jails. The report describes the characteristics of jail inmates in 2002, including offenses, conviction status, criminal histories, sentences, time served, drug and alcohol use and treatment, and family background. Characteristics of jail inmates include gender, race, and Hispanic origin. Changes since the 1996 inmate survey are examined. Data in 2002 were compiled from in-depth personal interviews with a nationally representative sample of nearly 7,000 inmates in about 417 local jails. Highlights include the following: Jail inmates were older on average in 2002 than 1996; 38% were age 35 or older, up from 32% in 1996. Half of all jail inmates in 2002 were held for a violent or drug offense, nearly unchanged from 1996. In 2002, 41% percent of jail inmates had a current or prior violent offense; 46% were nonviolent recidivists; 13% had a current or prior drug offense only. 07/14/04 NCJ 201932 Press release | Acrobat file (337K) | ASCII file (34K) | Spreadsheets (zip format 60K)

Statistics: State Prison Expenditures, 2001 Presents comparative data on the cost of operating the Nation's State prisons. The study is based on institutional corrections elements of the Fiscal 2001 Survey of Government Finances which State budget officers reported to the U.S. Census Bureau. State-level spending is presented on prison employee salaries and wages; employer contributions to employee benefits; supplies, contractual services, and other operating costs; and capital expenditures, e.g. building construction, renovations, major repairs, and land purchases. Additional data reveal amounts spent on food, inmate medical care, utilities, and contractual services. Highlights include the following: Prison operations consumed about 77% of State correctional costs in FY 2001. State correctional expenditures increased 145% in 2001 constant dollars from $15.6 billion in FY 1986 to 38.2 billion in FY 2001; prison expenditures increased 150% from $11.7 billion to $29.5 billion. Spending on medical care for State prisoners totaled $3.3 billion, or 12% of operating expenditures in 2001. 06/04 NCJ 202949 Acrobat file (197K) | ASCII version (42K) | Spreadsheets (zip format 53K)

U.S. Military Prisoners: Army Inspector General Inspection Report on Detainee Operations. An assessment of detainee operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. 2.2 Megabyte file. (July 22, 2004). [PDF]

U.S. Military Prisoners: Jose Padilla v. Commander C.T. Hanft, USN (July 2, 2004). [PDF] Alleged "dirty" bomb suspect Jose Padilla, a U.S. citizen detained in military custody as an "enemy combatant," has refiled his petition for writ of habeas corpus in the proper jurisdiction and against the proper respondent, following express instructions given by the U.S. Supreme Court in the recent case of Rumsfeld v. Padilla, No. 03-1027, 2004 U.S. Lexis 4759.

U.S. Military Prisoners: Documents and correspondence in the legal debate on the interrogation of prisoners in U.S. custody. Newly released documents from the U.S. Department of Justice and Department of Defense on the legality and use of certain interrogation techniques on prisoners and detainees in U.S. custody.

Reference:

• Abbreviations of Law Reports, laws and agencies used in our publications.