© Copyright 2004 by AELE, Inc.

Contents (or partial contents) may be downloaded,

stored, printed or copied by, or shared with, employees

of

the same firm or government

entity that subscribes to

this library, but may not be sent to, or shared with others.

A Civil Liability Law Publication

for officers, jails, detention centers and prisons

ISSN 0739-0998

Cite this issue as:

2004 JB Jul (web edit.)

Click here to view information on the editor of this publication.

Return to the monthly publications menu

Access the multi-year Jail & Prisoner Law Case Digest

Report non-working links here

Some links are to PDF files

Adobe Reader™

must be used to view content

Access

to Courts/Legal Info

Death Penalty

First Amendment

Mail

Medical Care

Medical Care: Dental

Prison Conditions: General

Prisoner Classification

Prisoner Suicide

Prisoner Transfer

Racial Discrimination

Segregation: Disciplinary

Strip Searches: Prisoners

Access to Courts/Legal Info

Assessment of Costs

Attorneys' Fees

Defenses: Statute of Limitations (2 cases)

Disability Discrimination: Prisoners

Employment Issues (2 cases)

False Imprisonment

Federal Tort Claims Act (2 cases)

Filing Fees

Medical Care

Prison Litigation Reform Act: Exhaustion of Remedies

Prisoner Assault: By Officers

Prisoner Death/Injury

Prisoner Discipline (4 cases)

Prisoner Suicide (2 cases)

Privacy

Racial Discrimination

Telephone Access

•••• Editor's Case Alert ••••

U.S. Supreme Court rules that states may be sued for damages under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) for acts of disability discrimination which allegedly interfere with the constitutional right of access to the courts, and that such claims are not barred by Eleventh Amendment immunity. Court does not provide a clear answer about whether similar lawsuits against governmental employees for damages are proper in other circumstances of alleged disability discrimination in the providing of public services or programs.

The plaintiffs, who are paraplegics, filed a lawsuit seeking money damages and injunctive relief under Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), 42 U.S.C. Sec. 12132, which prohibits disability discrimination against qualified individuals being excluded from "participation or denied the benefits of the services, programs or activities" of a public entity. They asserted that the unavailability of handicap access to certain Tennessee court facilities violated the ADA.

One of the plaintiffs claimed that he had to crawl up two flights of stairs to get to a courtroom in which he had to appear. The building did not have an elevator. When he later returned to the courthouse for a hearing, he refused to crawl again or to be carried by officers to the courtroom; he consequently was arrested and jailed for failure to appear. The other plaintiff, a certified court reporter, alleged that she has not been able to gain access to a number of county courthouses, and, as a result, has lost both work and an opportunity to participate in the judicial process.

The U.S. Supreme Court subsequently held in Board of Trustees of Univ. of Ala. v. Garrett, #99-1240, 531 U. S. 356 (2001), that the Eleventh Amendment bars private money damages actions for state violations of ADA Title I, which prohibits employment discrimination against the disabled. In the immediate case, however, a panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit rejected the application of the same rule to the plaintiffs' claims, stated that due process protects the right of access to the courts, and that the evidence before Congress when it enacted Title II established that physical barriers in courthouses and courtrooms have had the effect of denying disabled people the opportunity for such access.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in a divided 5-4 decision, upheld this result and found that, as applied to cases "implicating the fundamental right of access to the courts," Title II of the ADA was a valid exercise of Congress' authority under §5 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Congress, the 5 Justice majority found, enacted Title II of the ADA against a backdrop of "pervasive unequal treatment of persons with disabilities in the administration of state services and programs," including systematic deprivations of fundamental rights, such as access to the courts.

A Civil Rights Commission report before Congress showed that some 76% of public services and programs housed in state-owned buildings were inaccessible to and unusable by such persons. Title II was therefore an "appropriate response" to this "history and pattern" of unequal treatment. Justice Stevens wrote the majority opinion, in which Justices O'Connor, Souter, Ginsburg, and Breyer joined, with separate concurrences written by Justices Souter and Ginsburg.

While the case does not involve prisoners, the reasoning would appear applicable to disability discrimination claims brought by inmates.

Justices Rehnquist, Kennedy, Thomas, and Scalia dissented.

The Court's opinion does not appear, at this time, to furnish any guidance as to whether a majority of the Justices would reach the same result in disability discrimination cases involving the providing of governmental services and programs which do not relate to the fundamental constitutional right of access to the courts.

Tennessee v. Lane, #02-1667, 124 S. Ct. 1978 (2004).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet.

•Return to the Contents menu.

•••• Editor's Case Alert ••••

U.S. Supreme Court, in case involving death-row prisoner's challenge to Alabama state's use of a death penalty procedure requiring an incision into his arm or leg to access his severely compromised veins, rules that federal civil rights statute, 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1983 is an "appropriate" manner to assert an Eighth Amendment claim challenging confinement conditions in prison and seeking injunctive relief.

Three days before he was scheduled to be executed by lethal injection, an Alabama prisoner filed a civil rights lawsuit under 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1983 claiming that the use of a "cut-down" procedure requiring an incision into his arm or leg to access his "severely compromised veins" would be cruel and unusual punishment and "deliberate indifference" to his medical needs in violation of the Eighth Amendment.

The prisoner, who had already filed an unsuccessful federal habeas application, sought permanent injunctive relief against the "cut-down's" use, a temporary stay of execution so that a trial court could consider his claims, and orders to officials to provide a copy of the protocol on the medical procedures for venous access and directing them to promulgate a venous access protocol in compliance with "contemporary standards."

The defendants asked the trial court to dismiss the lawsuit for lack of jurisdiction, arguing that the Sec. 1983 claim and stay request were the equivalent of a second or successive habeas application subject to gatekeeping requirements under 28 U.S.C. Sec. 2244(b), requiring that an applicant obtain permission to pursue such additional habeas applications. The trial court agreed, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit upheld this decision.

A unanimous U.S. Supreme Court reversed, finding that a Sec. 1983 lawsuit was an "appropriate vehicle" for the prisoner's Eighth Amendment claim. Constitutional claims challenging conditions of confinement, rather than challenges to the fact of a prisoner's conviction or the "duration of his sentence" may properly be brought under Sec. 1983, the Court stated.

In so holding, the Court cautioned that it was not reaching the "difficult question" of how "method-of-execution" claims should generally be classified. It noted that the defendant officials had conceded that Sec. 1983 would be appropriate as an avenue for an inmate who was not facing execution to bring a "deliberate indifference" challenge to the cut-down procedure's constitutionality if it was used to gain venous access for medical treatment. The court found "no reason" to treat the claim differently for the sole reason that the plaintiff prisoner has been condemned to die.

The Court stated that the fact that access to the plaintiff's veins was necessary for the execution did not imply that a particular means of gaining that access was also necessary, and the plaintiff argued that it was not. The Court noted that the plaintiff was attempting to enjoin the use of the "cut-down" procedure, not his execution by lethal injection. At this point, the execution warrant has expired, and the Court stated that if the state rescheduled the execution while the case in pending on remand and the plaintiff "seeks another similarly broad stay," the trial court will need to address the issue of whether a request to enjoin the execution, rather than merely to enjoin an allegedly unnecessary precursor medical procedure, "properly sounds in habeas."

The Court also rejected arguments that its decision would "open the floodgates" to all manner of "method-of-execution challenges" and last-minute stay requests, stating that its holding was "extremely limited." Merely asserting a possible Sec. 1983 claim does not necessarily warrant a stay "as a matter of right." The Court also noted that the ability to bring a Sec. 1983 claim was still also subject to the substantive and procedural limitations of the Prison Litigation Reform Act.

Nelson v. Campbell, #03-6821, 124 S. Ct. 2117 (2004).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet.

•Return to the Contents menu.

Prisoner's inclusion of a false and irrelevant "rumor" concerning the sexual conduct of a female guard in a grievance he filed against her for allegedly failing to inform him that it was time to eat was not protected speech under the First Amendment.

An Illinois inmate sued prison employees, claiming that they had deprived him of his freedom of speech, in violation of the First Amendment by disciplining him for having included in a prison grievance that he filed an accusation of sexual misconduct by a prison guard. A federal appeals court upheld the dismissal of the claim.

In the prisoner's grievance, he had claimed that a female guard named Drone had "failed to notify him" that it was time to eat, but he also "embellished" the complaint with mention of a "rumor" that the guard was "screwing a lot of the Officer's on the midnight shift along with a few Sergeants and Lt's. etc." This resulted in an investigation of the "rumor," which was found to be baseless. The prisoner was then punished for violating a prison rule that forbids "insolence," defined as "talking, touching, gesturing or other behavior that harasses, annoys, or shows disrespect." Ill. Admin. Code title. 20, § 504, App. A. His punishment included being placed in disciplinary segregation for a week and loss of certain privileges.

The federal appeals court rejected the argument that the prisoner's inclusion of the false statements regarding the prison guard's alleged sexual activities was protected speech under the First Amendment.

The inclusion in Hale's grievance of the rumor of Drone's sexual misconduct was libelous, and even if a prison grievance were the legal equivalent of a pleading in court, a libel so unrelated to the subject of the pleading would not be privileged. Nor is a libel privileged by being labeled a "rumor" the accuracy of which the libeler declines to vouch for. [...] A "rumor" defense would be particularly unfortunate. It often is impossible to track down a rumor to its source; such a defense would therefore insulate many libels, however outrageous, from legal sanctions. As there is no indication that Hale had any basis for believing the rumor about Drone to be truthful, he was guilty of "actual malice" and so his libel was unprotected by the Constitution.

The appeals court also stated that these statements, in the context of a prison, would be unprotected even if the "actual malice" rule would privilege the repetition of the "rumor" in other settings. "Prison regulations that forbid inmates to behave insolently toward guards are constitutional irrespective of New York Times v. Sullivan," 376 U.S. 254 (1964), the court said. That case addressed issues of the appropriate constitutional standard for liability for defamation which concerns public officials, and established a requirement of "actual malice"--knowing falsity or reckless disregard of the truth--before such liability could be imposed.

Inmates' First Amendment rights must be exercised in a manner "consistent with prison discipline. And accusations of sexual misconduct "unrelated to the accusing inmate's legitimate concerns" (the prisoner was not accusing the guard of sexual harassment of him, for instances), are examples of punishable insolence. The plaintiff prisoner, the court stated, is like the "purveyor of pornographic pictures [who] pastes a copy of the Declaration of Independence on the back of each picture and argues that judged as a whole his product has redeeming social value." Groundless allegations in a legal pleading can be sanctioned, the court noted, "without anyone supposing that First Amendment are raised," so it would be "beyond paradoxical to suggest that if the allegations happened to be not only baseless but also libelous they would be entitled to greater protection."

Hale v. Scott, #03-1949, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 11581 (7th Cir. 2004).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

•••• Editor's Case Alert ••••

Prison did not violate inmate's rights by limiting his ability to correspond with family members in Spanish. Prisoner was fluent in English, and was allowed to correspond in Spanish with a family member who only knew that language. Rule limiting correspondence in foreign languages, subsequently abandoned, had been reasonably related to legitimate security concerns.

An Iowa inmate who was originally from Mexico City, Mexico, has a native language of Spanish, but he is also fluent in English. In accordance with prison policy, he submitted a formal request to write letters in Spanish to various members of his family. At the time, prison policy allowed written communication in a foreign language if that was the only language in which the inmate could communicate.

The prisoner's unit manager allowed him to write letters to his sister in Mexico City in Spanish because that was the only language in which communication could take place, but denied his request as to all other family members, including his mother, who lived in the U.S. The prisoner was also not allowed to receive letters in Spanish from those family members. He filed a grievance challenging the unit manager's application of the rule. While this grievance was pending, the prison changed its policy and permitted all inmates to correspond "in their preferred language," so that the prisoner was allowed to correspond in Spanish with all family members.

He filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the facility and the unit manager asking for compensatory and punitive damages for the First Amendment violation he claimed occurred during the three months that he was unable to write or receive letters to or from certain family members in Spanish. The trial court found that the former policy of preventing such communications as part of monitoring prison mail was "reasonably related to a penological interest" and therefore found in favor of the defendants.

A federal appeals court has upheld that result. While prisoners have a right to send and receive mail, prison officials have a legitimate interest in monitoring that mail for security reasons. The fact that the plaintiff prisoner identified several avenues by which an inmate could still plan an escape route or smuggle items into the prison even with the imposition of the English-only rule (such as speaking in Spanish on the phone) did not mean that the policy "was not rationally related to lessening those risks," the court reasoned.

The appeals court also noted that the facility changed its policy because of an "influx" of foreign-speaking inmates. "Instead of indicating that its policy was never related to a legitimate interest," as the prisoner suggested, the court stated, "we view this shift in policy as a constructive and continuing attempt" by the prison to "balance competing First Amendment concerns with safety concerns."

The prisoner had other avenues to communicate with family members, including in-person visits and phone calls. The appeals court also noted that the plaintiff prisoner did not identify a "cost-free way" for the prison to accommodate him. He did not introduce any evidence of what the cost of hiring an interpreter would have been, whether the prison had any Spanish-speaking employees, whether other prisons could have interpreted the letters, or whether a social service agency was willing to translate the letters on the prison's behalf. Without proof of such a ready alternative, the prisoner did not show that accommodation of his request would not be burdensome.

Ortiz v. Fort Dodge Correctional Facility, #03-1868, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 10200 (8th Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Prisoner's claim that doctor and physician's assistant repeatedly refused to examine him for complaints of back pain and injuries from fall was sufficient to state a claim for deliberate indifference. Plaintiff adequately exhausted available administrative remedies despite his failure to ask for money damages in filed grievances, when grievance procedure did not require him to ask for any specific remedy at all.

An inmate in the custody of the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against four defendants at the State Correctional Institution at Coal Township, Pennsylvania, two prison officials, a prison doctor and a prison physician's assistant (Brian Brown). He alleged that, as a result of the defendants' deliberate indifference, his serious back condition was left untreated, or was inadequately treated, resulting in "excruciating pain and susceptibility to other injuries."

He had filed a series of three inmate grievances concerning the medical treatment, and ultimately received some measure of medical care. The grievances did not seek money damages, but he subsequently sought such damages in his lawsuit.

Under 42 U.S.C. § 1997e(a) of the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA), a prisoner may not bring a lawsuit with respect to prison conditions without first exhausting available administrative remedies. The trial court concluded that the prisoner had failed to meet this exhaustion requirement because he failed to seek money damages in his grievances, and therefore dismissed the entire lawsuit. The trial court also found that the prisoner's failure to name one of the defendants in his grievances constituted a failure to exhaust his administrative remedies towards that defendant.

On the prisoner's appeal, a federal appeals court stated:

Courts have only recently begun to define the contours of the PLRA's exhaustion requirement, and we have not had occasion to pass on whether the exhaustion requirement is merely a termination requirement or also includes a procedural default component--that is, whether a prisoner may bring a § 1983 suit so long as no grievance process remains open to him, or whether a prisoner must properly (i.e., on pain of procedural default) exhaust administrative remedies as a prerequisite to a suit in federal court. This case requires us to confront that issue, and we hold that § 1997e(a) includes a procedural default component. We further hold that the determination whether a prisoner has "properly" exhausted a claim (for procedural default purposes) is made by evaluating the prisoner's compliance with the prison's administrative regulations governing inmate grievances, and the waiver, if any, of such regulations by prison officials.

What this meant in the immediate case, the court found, is that the prisoner was not required to seek money damages in his grievances, and therefore had not "procedurally defaulted" his claim for such damages, that the prisoner was required to name each defendant in his grievances, but that the officials handling the grievances waived his default in failing to name one of the defendants (the physician's assistant), and that the prisoner did properly exhaust his administrative remedies under the available grievance policy. The applicable state rules regarding prisoner grievances did not require him to ask for any particular remedy at all--merely to state the specifics of his complaint and the persons responsible or with information regarding the incident. While he did fail to specify the name of the physician's assistant in his grievances, the name was added by those processing the grievance itself.

Turning to the substance of the claims, the appeals court also found that the prisoner, while failing to state a claim against the officers, did state a possible claim against the defendant doctor and physician's assistance.

The prisoner had complained about pain from a chronic back problem upon arriving at the facility, and subsequently suffered further injuries from a fall. He claimed that he was not examined by a doctor despite his requests for such care, and that when the defendant doctor later came to his cell in response to a sick call request, he refused to examine him, and stated that he would "never go to the infirmary." The prisoner claimed that the doctor's visit "lasted approximately 30 seconds" or less.

When he was subsequently seen by the physician's assistant, he claimed, he was accused of faking his injuries and was again not examined. While he was furnished with some medication, his complaints that the medication was not helping was allegedly ignored, and when he subsequently saw the doctor, the doctor stated that he did not believe that there was "anything wrong" with his back, and accused him of "playing games."

The doctor allegedly again failed to examine the injuries sustained in the fall.

The federal appeals court found that the prisoner's factual allegations, if true, could constitute deliberate indifference to serious medical needs. The prisoner claimed that the doctor and physician's assistant acted "maliciously and sadistically," refusing to examine him on multiple occasions, instead accusing him of faking his injuries. Additionally, he also claimed that when the doctor ultimately did examine him, he twisted his legs "as if he was trying to shape a pretzel," and told the doctor repeatedly that the examination was causing additional pain to his back and leg.

The prisoner connected his factual allegations to the alleged mental states of the doctor and physician's assistant, claiming that their actions were not only deliberately indifferent, but malicious and sadistic. Taking those claims as true for purposes of the appeal, the appeals court reversed the dismissal of the lawsuit against those two defendants.

Spruill v. Gillis, #02-2659, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 12027 (3rd Cir. 2004).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Inmate's claim that prison doctor and nurse failed to arrange for dental care for him for six weeks after his written request stated a possible claim for deliberate indifference to his serious medical needs.

An Iowa inmate claims that he first submitted a written medical request asking to be examined by a jail nurse and doctor on October 20, 2001, claiming that he was suffering a severe toothache and three loose teeth, but that his complaints were ignored. He finally received treatment from a dentist on December 5, 2001, the inmate asserted, and the dentist told him that the delay had caused a bad infection in his mouth. The dentist pulled three of his teeth and prescribed antibiotics and ibuprofen.

The prisoner sued, claiming that the nurse and doctor had been deliberately indifferent to his serious medical needs and that the jail had a policy or custom of not providing adequate treatment for pretrial detainees in order to save money.

Overturning summary judgment for the defendants, a federal appeals court noted that the plaintiff presented evidence that he suffered extreme pain from loose and infected teeth, which caused blood to seep from his gums, swelling, and difficulty sleeping and eating. This was a serious need for medical attention that "would have been obvious to a layperson, making submission of verifying medical evidence unnecessary."

Further, the prisoner claimed that the nurse ignored his repeated complaints and requests for medical attention, and that the doctor did nothing when contacted about his condition. The doctor allegedly withheld dental treatment for "nonmedical reasons" such as the prisoner's behavioral problems. There was a factual issue, therefore, whether these defendants were deliberately indifferent to the prisoner's serious medical needs when they failed to arrange for dental treatment until about six weeks after his written request for it, causing him to suffer further pain and infection.

Hartsfield v. Colburn, No. 03-2602, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 11572 (8th Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Prisoner's claim that he was subjected to "standing water" in a prison shower area resulting in a fall was insufficient to establish a claim for cruel and unusual conditions of confinement posing a substantial risk of serious harm to his health or safety. Despite the fact that prisoner was on crutches, the danger of falling on a slippery floor was no greater than the daily hazards faced by the general public.

A prisoner in a maximum security Utah facility sued correctional officers, claiming that they violated his Eighth Amendment right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment by subjecting him to a hazardous condition in the prison shower area, involving "standing water."

The trial court found that the plaintiff had presented sufficient evidence to establish an Eighth Amendment violation, but that the officers were entitled to qualified immunity because the law governing their conduct was not clearly established at the time of the violation.

A federal appeals court agreed that the officers were not liable, but also found that the plaintiff had put forth insufficient evidence to establish a violation of the Eighth Amendment to begin with, eliminating the need to address the issue of qualified immunity.

The plaintiff prisoner claimed that he suffered significant injury to his head, neck, and back when he fell in the prison shower, due to the fact that the shower area in the prison failed to drain properly and water accumulated in a depression outside the shower area. He claimed that he warned the defendant officers of this problem several times before and specifically warned them that he was at a heightened risk of falling because a previous injury required him to use crutches. He also claimed that before he fell he asked for extra towels to clean up the water, but one of the defendant officers denied the request, instead instructing him to "be careful." The prisoner also claimed that another inmate slipped and fell in the shower area prior to him.

The plaintiff was required to show that the standing-water problem rose to the level of a condition posing a substantial risk of serious harm to inmate health or safety. The appeals court found that he had not.

To begin with, while the standing-water problem was a potentially hazardous condition, slippery floors constitute a daily risk faced by members of the public at large. Federal courts from other circuits have therefore consistently held that slippery prison floors do not violate the Eighth Amendment. Simply put, "[a] 'slip and fall,' without more, does not amount to cruel and unusual punishment. . . . Remedy for this type of injury, if any, must be sought in state court under traditional tort law principles." Thus, the question is whether this case presents sufficiently special or unique circumstances that require us to depart from the general rule barring Eighth Amendment liability in prison slip and fall cases.

The plaintiff claimed that his situation was distinguishable from a typical prison slip and fall case because he was on crutches and had specifically warned the officers that he was at a heightened risk of falling prior to the incident. The appeals court disagreed. It was undisputed that the plaintiff first became aware of the standing-water problem seven weeks before he fell, and that he had safely entered and exited the shower area on crutches on numerous occasions prior to his fall.

Consequently, we conclude, as a matter of law, that the hazard encountered by plaintiff was no greater than the daily hazards faced by any member of the general public who is on crutches, and that there is nothing special or unique about plaintiff's situation that will permit him to constitutionalize what is otherwise only a state-law tort claim.

Reynolds v. Powell, #03-4156, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 10838 (10th Cir.).

» Click here to read the text of the opinion on the Internet.

•Return to the Contents menu.

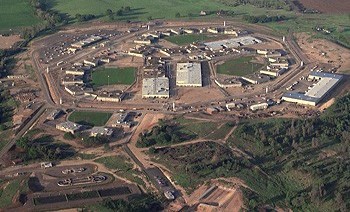

Ohio prisoners had a protected liberty interest in not being placed in a "supermax" high-security facility without due process. Federal appeals court upholds trial judge's injunctive orders concerning procedures to be followed prior to placement, including specific notice of grounds for placement and evidence to be relied on, but also finds that trial court went too far in modifying substantive state regulations, such as specifying the amount of drug possession or level of gang involvement required before placement in the "supermax" facility.

A number of prisoners at the Ohio State Penitentiary in Youngstown, Ohio, filed a federal civil rights class action lawsuit claiming alleged procedural due process claims relating to their placement at the OSP facility, which is a supermaximum, or "supermax," facility. Their due process claims for declaratory and injunctive relief were then tried by a federal trial court, which entered a judgment for the prisoners and issued injunctive orders.

A federal appeals court upheld the finding that the prisoners had a constitutionally protected liberty interest in the prison placement at issue and in modifying the procedures that govern that placement, but also held that the trial court erroneously modified "substantive Ohio prison regulations," requiring the reversal of a portion of the injunctive orders.

The goal of the facility was to separate the most dangerous prisoners from the rest of the prison population, a goal achieved primarily through solitary confinement. Prisoners at OSP spend twenty-three hours a day in their single cells, measuring approximately 89.7 square feet, and metal strips on the bottom and sides of the cell doors prevent the prisoners from communicating with each other. Limited recreation is available during the one hour a day prisoners can leave their cell, and most have recreation alone. Prisoners are strip-searched when they have visitors, and there are extra limitations on personal property rights, access to telephones and lawyers and communications with other persons. OSP prisoners are also ineligible for parole.

Factors involved in the decision to place prisoners there following reclassification include their age, the severity of the offense triggering the initiation of reclassification hearings, prior prison experience, prior violent behavior, pre-prison gang activity, and escape attempts, but prison officials can override the numerical score for any of the reasons identified as the grounds for a high security level classification. These include assaultive and/or predatory behavior; the nature of the inmate's conviction; leadership roles in riots or disturbances; the possession of contraband; the identification of the inmate as a leader of a "security threat group" (prison gang); escape attempts; "an ability to compromise the integrity of [prison] staff"; knowing exposure of others to HIV or hepatitis; or a chronic inability to adjust to a lower security level.

If the warden approves a recommendation that the prisoner be placed at OSP, the approval and recommendation are forwarded to the department's Bureau of Classification for a final decision, and the prisoner is given 15 days to file a formal objection. After thirty initial days at OSP, the staff there reviews the placement, and if they and the OSP warden agree to recommend a security reduction, this is sent to the Bureau. Review of OSP inmates' security levels are reviewed at least annually.

The trial court found due process deficiencies in the procedures, including inmates not being given notice of all evidence that may be relied upon in their classification hearings, inmates not being allowed to call witnesses, and the placement criteria giving insufficient notice of the amount of drugs in possession that would trigger the placement. The court also found that the placement criteria were unnecessarily vague with regard to the gang activity that would trigger a placement at OSP, and that the final decisionmaker, the Bureau of Classification, was not required to describe the facts found and reasoning used in making its decision.

The trial court ordered that the defendants correct each of these deficiencies.

The appeals court agreed that the conditions at the "supermax" OSP, compared to the conditions at other Ohio prisons, specifically in the segregated units of maximum-security prisons, all combined to "create a significant and atypical hardship." As a result, Ohio prisoners have a constitutionally protected liberty interest in not being placed there in the absence of the state-mandated "substantive predicates" set out in the correctional department's policy.

Before the trial court's injunctive orders, which modified the application of this policy, inmates could be placed at OSP for any contraband activity, the appeals court noted, no matter how minimal. The trial court directed that the policy be rewritten to specify a quantity of contraband activity, and for drug activity, the trial court stipulated that the threshold amount should reflect a level that would subject a prisoner to incarceration "for at least a third degree felony," or else be based on multiple violations involving lesser quantities of drugs. The trial court's orders also required that the policy be modified to require a greater showing of involvement in security threat groups, such as gangs, before placement at OSP. The trial court also required that only behavior in the past five years should be considered prior to a retention decision, and that an inmate with three years free of violent behavior and two years free of major misconduct "should generally qualify for reclassification" to a lower level and transfer out of OSP, unless his prior conduct resulted in death or extreme bodily harm.

The appeals court found that these modifications went too far.

The power of the federal courts to order modifications in state prison policies extends only as far as is necessary to protect federal rights. The Inmates do not argue and we do not decide whether placement at OSP implicates either the Eighth Amendment or the substantive portion of the Due Process Clause. The federal right at issue in this case, then, is defined solely in relation to the substantive limits placed on the discretion of the ODRC officials by state law itself. Therefore, the district court only had the power to order federally mandated process in a substantive inquiry otherwise governed by the state. The district court was thus without power to order the state officials to modify the substantive predicates which governed placement and retention at OSP.

Accordingly, regardless of the soundness of any particular modification made by the trial court, those modifications were improper.

While the trial court correctly identified adequate notice as a due process requirement, the appeals court concluded that the regulations provided sufficient notice and that the modifications were in fact substantive modifications. Under the original regulations, it was clear that any amount of drugs could trigger a reclassification hearing, for example, so that altering the specified amount did not "improve" upon the notice provided, but instead limited the substantive discretion of the prison officials.

The appeals court upheld, however, certain procedural changes ordered by the trial court, such as limiting the placement decision to matters detailed in the notice given to the inmate. The appeals court rejected the argument that this improperly decreased the ability of the correctional officials to rely on "rumor, reputation, and even more imponderable factors," since those factors "are illegitimate under their own placement scheme." A written notice of the grounds believed to justify placement at OSP and a summary of the evidence to be relied on was not overly burdensome.

Austin v. Wilkinson, #02-3429, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 11414 (6th Cir.).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the Internet.

•Return to the Contents menu.

Federal appeals court upholds wrongful death jury award of $1.75 million in Illinois detainee suicide case based on alleged custom of failing to follow proper procedures with mentally ill inmates.

A 23-year-old pre-trial detainee hanged himself with a bed sheet at a Lake County, Illinois jail. The detainee's estate sued a private contractor hired by the county to provide medical and mental health services at the jail, as well as a number of its employees--a nurse, a social worker, and a doctor. Claims were asserted both for alleged violations of federal civil rights and for wrongful death under a state statute.

Prior to trial, the county sheriff and a deputy who were also named as defendants in the case settled with the estate and the estate dismissed its state law wrongful death claims against the remaining defendants. A jury found that the private contractor and its social worker acted with deliberate indifference to the detainee's health and safety, while returning a verdict for the doctor and nurse. It awarded compensatory damages of $250,000 and punitive damages against the contractor of $1.5 million.

A federal appeals court upheld these awards. Despite the contractor's explicit recognition, in various documents and training materials, that the risk of suicide presented a "unique and critical problem in a jail," the evidence at trial, the court found, showed that the contractor "routinely failed" to comply with its own directives on how risks were assessed and monitored. One of its nurses testified that the environment at the jail was "very lack, unprofessional," and that she was only made aware of the policies and procedures manual after she asked for it. Additionally, she testified that the contractor's personnel "purposely delayed" ordering prescribed medication for inmates in hopes that they would be transferred to the Department of Corrections and out of their care.

The contractor also allegedly had a routine "month-long" backlog of intake evaluation of inmates, contrary to its written policies and procedures. One nurse also testified to seeing another nurse under the influence of drugs and incapable of performing her duties, but that this and other similar problems were ignored, with a supervisor telling her she should simply go home if she "did not like" to work with impaired nurses.

When the detainee arrived at the jail, charged with the attempted sexual assault of his 12-year-old niece, he was screened by a nurse who had never before done a mental health intake screening and who had "no prior experience in psychiatric nursing, mental health nursing, jail nursing, or suicide diagnosis." Further, she had not completed the contractor's 90-day orientation program, had not viewed an intake screening videotape used for training, and had never read the contractor's policies and procedures relating to intake screening identifying risks of suicidal behavior, or handling identified suicidal prisoners.

She checked off "yes" to the question as to whether the prisoner "expresses thoughts of killing self," and noted that he had a history of psychiatric treatment and suicide attempts, but failed to complete the form by indicating that he presented a suicide risk in the "summary" or "disposition." She also failed to alert the jail's shift commander about the detainee's condition or refer the detainee for an immediate mental health evaluation.

The detainee was therefore placed into the jail without suicide precautions and was not put on the jail's suicide watch list. Later testimony from the nurse's direct supervisor indicated that this failure to initiate suicide prevention measures was consistent with "standard operating practice" at the jail.

The detainee was, however, placed in a cell in the jail's "medical pod" because he had cerebral palsy. Despite an alleged policy by the contractor requiring a prompt mental health evaluation soon after the initial screening, the detainee was not evaluated by the contractor's social worker until seven days. This social worker allegedly did not review the detainee's medical chart before interviewing him, and therefore did not see the intake screening form documenting the prisoner's history of mental health problems, psychiatric hospitalizations and suicide attempts.

The social worker testified that it was not his regular practice to review the charts prior to conducting a mental health evaluation, and even described this as clinically beneficial and allowing him to "get a fresh impression." He also indicated that his workload presented a time pressure that prevented him from "going back and checking on everything." His direct supervisor approved of this habit of not reviewing an inmate's chart prior to conducting the evaluation. The social worker also stated that immediately before he evaluated the detainee, someone in the jail heard him expressing suicidal thoughts, and that it had "never crossed his mind" that the detainee was "not on suicide watch."

His evaluation included notations about the detainee's ten prior psychiatric hospitalizations, the most recent following a suicide attempt, and a recommendation that he be referred to the contractor's psychiatrist. This was not done until 7 days later, which was fourteen days after he arrived at the jail. The social worker also allegedly did nothing to see that the detainee was placed on suicide watch or housed in a safe cell pending a psychiatrist's examination.

The psychiatrist noted that the detainee was expressing "suicidal ideation," and diagnosed him as suffering from a major depressive disorder and possibly a bipolar disorder. But, like the nurse and social worker, the psychiatrist allegedly did nothing to ensure that the detainee was put on suicide watch and did not review available records to determine his custody status or take any action to make sure that suicide prevention steps were taken. He prescribed medication, but later acknowledged that it would take at least several days and as long as a number of weeks, for this medication to become effective.

The detainee later hung himself from a bed sheet slung around four garment hooks attached to his cell wall and died.

An expert witness had "no quarrel" with the contractor's suicide prevention procedures, screening form, and instructional video, but testified that the problem was that the company "systematically ignored its own suicide prevention procedures." He stated that the detainee came in "almost screaming for help," and that he had "never seen [a suicide risk] that was more [clearly documented] than this case."

The appeals court ruled that there was enough evidence for a reasonable jury to conclude that the contractor's actual practice, as opposed to its written policy, towards the treatment of mentally ill inmates was "so inadequate" that it was on notice at the time the detainee was incarcerated that there was a substantial risk that he would be deprived of necessary care in violation of his Eighth Amendment rights.

The appeals court rejected the argument that the contractor could not be held liable because of the plaintiff's failure to introduce evidence of any prior suicide at the jail. The defendant, the court commented does not get a "one free suicide" pass. Given the evidence, the court stated, the fact that no one in the past committed suicide simply showed that the contractor was "fortunate, not that it wasn't deliberately indifferent."

For all intents and purposes, ignoring a policy is the same as having no policy in place in the first place.

The appeals court also rejected the defendant's claim that the punitive damages award was inappropriate under the circumstances.

Woodward v. Corr. Med. Services of Illinois, #03-3147, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 9537 (7th Cir.).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Washington state prisoner did not have a constitutional right to imprisonment in a specific facility and therefore was not entitled to challenge an administrative decision transferring him to a privately-run prison in another state.

A Washington state prisoner filed a habeas corpus petition challenging the state's authority to continue to confine him after his transfer from a Washington state prison to a privately-run prison in Colorado. The challenge was not to his conviction, but merely to the administrative decision to transfer him from one prison to another. He filed the federal habeas petition after exhausting available state remedies and proceedings.

A federal appeals court upheld the denial of his petition because the prisoner had "no constitutional right to imprisonment in a specific prison. The transfer was done to help alleviate overcrowding

The appeals court found that the transfer did not violate any substantive liberty interest protected by due process, rejecting the prisoner's argument that it did because the transfer made him unable to receive visitors or see counsel because of the distance involved.

White v. Lambert, #02-35550, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 11427 (9th Cir.).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

If race was the only criteria used to exclude black inmates from a critical worker list of those allowed to return to their prison jobs during three lockdowns, then plaintiff prisoner was not required to prove discriminatory intent in his racial discrimination lawsuit.

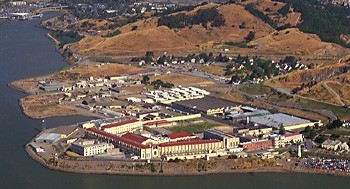

An African-American inmate in California claimed that he was denied equal protection because, during three prison lockdowns, he was not allowed to resume his prison job until after similarly-situated prisoners of other faces. The plaintiff prisoner is serving a life sentence in Calipatria State Prison. He was assigned to be a clerk in the law library in one of four separate facilities or yards into which the prison is divided, and was eventually promoted to lead law library clerk.

The facility has a history of racial tension and violence and sometimes the prison was placed on lockdown after fights involving prisoners of different races. On one such occasion, several Hispanic and black prisoners were involved in a fight, and all prisoners were then restricted to their cells and not permitted to exercise. Only Hispanic and black inmates, however, were also excluded from "critical-workers" list--a category of workers approved to continue attending their job assignments despite the lockdown. The plaintiff was not permitted to return to his library assignment for almost a month, three weeks longer, he claims, after a white inmate who served as an assistant clerk had been allowed back to work.

The plaintiff prisoner asserts that he is not a gang member. The lawsuit focuses on three lockdowns after three separate incidents which took place in 1995, in which prisoners attacked staff members. In the first incident, five black gang members attacked staff members in the same yard in which the plaintiff was confined. Days after the incident, limited groups of critical workers were allowed to go to their jobs, including clerks, in-grounds work crews, central kitchen, laundry, yard crews, visiting porters and canteen clerks. But black inmates were not eligible to be "critical workers," and the plaintiff was not returned to his job assignment until weeks later.

A second incident involved three black inmates who were members of two gangs attacking staff members in front of a dining room. Following this incident, black inmates were only authorized for eligibility for the critical-workers list after a central file review. In the third incident, a group of black gang members stabbed a staff member, and the prison was again placed on lockdown, and the plaintiff was again allegedly told that black inmates were not eligible to be placed on the critical-workers list, with the plaintiff kept off of his job for at least a week. Both the second and third attacks took place in a yard other than the one in which the plaintiff was confined.

A federal appeals court has overturned summary judgment for defendant prison officials in a racial discrimination lawsuit filed by the prisoner. The trial court had held that the prisoner had failed to show that the defendants acted with the required discriminatory intent needed to state a claim.

The appeals court disagreed, noting that racial discrimination in prisons and jails is unconstitutional under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment except for the "necessities of prison security and discipline."

The plaintiff prisoner did not dispute the validity of confining all prisoners to their cells as part of a prison-wide lockdown after the violent incidents, the court noted. "He claims, instead, that defendants discriminated against him by employing race to determine threshold ineligibility for placement on critical-workers lists during lockdown periods." While there is no right to prison employment, racial discrimination in the assignment of jobs also violates equal protection, the court stated.

The appeals court found that it was "clear" from the evidence submitted that the defendants "explicitly considered race in determining threshold ineligibility for critical-worker status." Since the defendants essentially admitted that they used race as the "only factor" in preliminarily excluding the black inmates from the critical-workers lists, the plaintiff was not required to prove discriminatory intent. The fact that the defendants said they employed racial classifications for the alleged purpose of promoting safety did not alter the result.

At the same time, the court also found that it had not previously been clearly-established that race-based differentiation is unconstitutional in the context of a prison-wide lockdown instituted in response to gang- or race-based violence, so that the individual defendants were entitled to qualified immunity from liability for damages. The court cautioned, however, that this did not mean that they could not be enjoined from future violations of the plaintiff's rights.

Walker v. Gomez, #99-55265, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 11157 (9th Cir.).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Hearing officer in disciplinary hearing which resulted in sentence of prisoner to 90 days of confinement in Special Housing Unit was not entitled to qualified immunity on prisoner's due process claim challenging alleged procedural defects in the hearing, including purported intentional erasure of a portion of a tape of the hearing containing exculpatory testimony.

A New York state prisoner and a corrections officer had a physical altercation, which they gave conflicting accounts of. The officer charged the prisoner with various infractions, including refusing a direct order, violent conduct, and harassment. A Deputy Superintendent presided over a disciplinary hearing on those charges and found the prisoner guilty, penalizing him with 90 days in keeplock and denial of access to packages, the commissary and the telephone for 90 days. The prisoner served 77 days in the Special Housing Unit (SHU) of a different prison, where he was denied any personal property, including personal food, clothing, grooming and hygiene products) and he was placed in restraints whenever he was escorted outside his cell. This also resulted in the end of his participation in the Family Reunion Program, through which he had previously enjoyed extended visits with his wife and children in a trailer outside the prison cellblocks.

In the process of appealing the disciplinary decision, the prisoner realized that a portion of the tape of the hearing, containing the purportedly exculpatory testimony of another corrections officer was inaudible, although the testimony immediately before and after that was clear. The prisoner claimed that the hearing officer, realizing that he "could not be convicted" in light of this testimony, intentionally erased the testimony so that his verdict would be sustained on review.

Ultimately, because of the defective hearing tape, the disciplinary finding was reversed and the hearing's outcome expunged from the prisoner's record. The prisoner then sued the correctional officer and the hearing officer, claiming a violation of his due process rights by intentional erasure of the tape of the hearing.

A federal appeals court has rejected the hearing officer's claim that he was entitled to qualified immunity because the prisoner's confinement in a SHU for 77 days was too brief to implicate a constitutionally protected liberty interest. The court found that the length of the sentence, combined with the expulsion from the Family Reunion Program, as well as factual disputes over the severity of the conditions of the prisoner's confinement there, presented an issue as to whether the confinement could amount to an "atypical and significant hardship."

The appeals court noted that in the absence of a detailed factual record concerning the conditions of confinement in an SHU, it had previously affirmed the dismissal of due process claims only in cases where the time spent in such confinement was extremely short, such as less than 30 days.

Palmer v. Richards, #03-290, 364 F.3d 60 (2nd Cir. 2004).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Strip search following which prisoner was required to stand naked in a bathroom stall for twenty minutes until he could produce a urine sample for random drug testing was not cruel and unusual punishment. Search was for the legitimate purpose of preventing the contamination of the urine samples, and correctional officer conducting the search did not act in any improper manner.

A Wisconsin prisoner was strip searched as part of a random drug-testing program and made to stand naked for twenty minutes in a bathroom stall until he produced a urine sample. He filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the correctional officer who conducted the strip and body-contents search, and against the prison's security director.

The prisoner, who has served approximately twelve years in the Wisconsin state prison system, admitted that he had been strip searched possibly dozens of times without complaint. But he claimed that this search was "cruel and unusual punishment" in violation of the Eighth Amendment because it was unnecessary in conjunction with routine drug testing and because of the length of time he was made to stand naked while attempting to produce the required sample.

A federal appeals court, upholding a trial court decision, rejected all of these claims.

The prisoner was woken by the officer at around 3 a.m. for the random drug testing, and was escorted to the common bathroom facilities used by inmates. The prisoner entered a bathroom stall and completely disrobed for a strip search, which consisted of a visual inspection of his nude body for contraband substances that could be used to contaminate the urine sample. It involved the prisoner showing the officer his hands, inside of his mouth, ears, bottoms of his feet, anus, and under his testicles. The officer then handed the prisoner the specimen bottle.

The prisoner could not produce the sample right away and asked that he be allowed to dress, but the officer instructed him that he could not do so until he produced the urine sample. This allegedly took him approximately 20 minutes. During that time, the prisoner subsequently acknowledged, the officer "did not touch him, ridicule him, make fun of him, express any anger toward him, or threaten him. The prisoner complained only that the officer "hovered" outside the stall, making it difficult to provide the sample. The officer was required to watch the urine being deposited into the bottle, to ensure that the sample was not contaminated or substituted.

The appeals court found no malicious motive or purpose of harassment here. It found that the strip search at issue was plainly constitutional. The purpose of the strip search was to reduce the opportunity for inmates to contaminate or substitute their urine samples and thwart the prison's attempts to maintain a drug-free facility.

As for the prisoner's claim that he felt "humiliated" by the twenty-minute period he remained naked until he produce a sample, the appeals court noted that a prisoner's expectation of privacy is "extremely limited" in light of the overriding need to maintain institutional order and security.

Being made to stand naked twenty minutes as part of a random drug-testing policy is not a "sufficiently serious" condition of confinement to rise to the level of a constitutional violation.

Given that the strip search was for a legitimate purpose, and that the officer conducting it did not act improperly in any way, the prisoner simply had no claim.

Whitman v. Nesic, #03-2728, 2004 U.S. App. Lexis 9631 (7th Cir.).

»Click here to read the text of the decision on the Internet. [PDF]

•Return to the Contents menu.

Report non-working links here

Access to Courts/Legal Info

Prison mailroom personnel did not violate prisoner's right of access to the courts even if they deliberately delayed mailing certain items to the court in his ongoing federal lawsuit, and even if this delay caused him to miss court deadlines. The prisoner's case was ultimately dismissed on its merits after a bench trial, and not on the basis of the missed court deadlines, so that the defendants' actions did not result in any prejudice to his case. Deleon v. Doe, #03-0093, 361 F.3d 93 (2nd Cir. 2004).

Assessment of Costs

City jail's practice of assessing state prison inmates held there a $1 per day room and board fee, under the authority of a state statute did not violate their constitutional rights against cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment or constitute an "excessive fine" (indeed, it was not a "fine" at all, but merely the recoupment of expenses from prisoners with funds). Failure of jail to similarly impose such a fee on federal prisoners held in the facility did not violate equal protection, and it did not violate due process for the jail to fail to provide inmates with a "post-deprivation hearing" on the imposition of the fee. Waters v. Bass, 304 F. Supp. 2d 802 (E.D. Va. 2004).

Attorneys' Fees

Prisoner awarded $1,000 against one of two defendant correctional officers on his claim for excessive use of force against him was also entitled to $1,500 in attorneys' fees as a prevailing party under 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1997e(d) (2) limiting awards against defendants for attorneys' fees to 150% of award for damages. Farella v. Hockaday, 304 F. Supp. 2d 1076 (C.D. Ill. 2004).

Defenses: Statute of Limitations

Statute of limitations on prisoner's disability discrimination claim based on his dismissal from prison job was tolled (extended) under Pennsylvania state law during the time that a prison official delayed filling out an administrative complaint form, even though the delay was not intentional, but merely negligent. Limitations period was also extended during the time that the prisoner pursued the exhaustion of his available administrative remedies as required by 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1997e(a). Howard v. Mendez, 304 F. Supp. 2d 632 (M.D. Pa. 2004).

Federal prisoner who claimed he lacked knowledge of the identities of the correctional officials who were involved in the use of excessive force against him and deliberate indifference to his medical needs was not entitled to an extension of the applicable statute of limitations within which to bring his lawsuit on the basis of "fraudulent concealment," in the absence of any showing that any officials deliberately concealed any information from him relating to his claims. Garrett v. Fleming, #03-1143, 362 F.3d 692 (10th Cir. 2004).

Disability Discrimination: Prisoners

Prison officials' alleged refusal to treat inmate's hepatitis B and C by medicating him with interferon did not constitute deliberate indifference to his serious medical needs and was not disability discrimination in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), 42 U.S.C. Sec. 12101 et seq. Evidence was insufficient to show that the plaintiff's hepatitis was severe enough to require such "extraordinary" treatment under generally accepted medical standards, and prisoner failed to show that he was denied the requested treatment solely because of his disability of mental illness. Davidson v. Texas Dept. of Crim. Justice, #03-41185, 91 Fed. Appx. 963 (5th Cir. 2004). [PDF]

Employment Issues

Arbitration award upholding suspension of corrections officer for three and a half months without pay for refusing to simultaneously escort two diabetic inmates to facilities "insulin room" could not be overturned on "public policy" grounds. While the officer claimed that the order was unlawful under a prison rule requiring prisoners to be escorted to the insulin room "individually," he failed to show that the rule was aimed at prison safety, and there was evidence that the rule was enacted to ensure accurate accounting and disposal of syringes used by inmates who self-administered insulin while medical personnel was not available. Selman v. Department of Correctional Services, 773 N.Y.S.2d 364 (A.D. 1st Dept. 2004).

County sheriff was not entitled to qualified immunity from lawsuit by correctional officer for violation of his First Amendment rights and wrongful termination in violation of public policy by firing him after he complained about fellow officer's alleged illegal conduct while transporting an extradited prisoner. Trial court judge upholds jury awards of $88,027 for past lost wages and benefits, and $40,000 for future lost wages and benefits, but orders new trial on jury's "excessive" $250,000 award for emotional distress unless plaintiff officer agrees to a reduced amount of $130,000. Shepard v. Wapello County, Iowa, 303 F. Supp. 2d 1004 (S.D. Iowa 2003).

False Imprisonment

County sheriff was not entitled to summary judgment in lawsuit seeking damages for continued detention of arrestee after release notice was allegedly received, based on factual disputes about when the notice was actually received and whether there was deliberate indifference to the plaintiff's right to release from incarceration at that time. Green v. Baca, 306 F. Supp. 2d 903 (C.D. Cal. 2004).

Federal Tort Claims Act

Statute of limitations on former federal prisoner's claim against the U.S. government under the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA), 28 U.S.C. Secs. 1346, 2671 et seq., for negligence in miscalculating his release date began to run when he obtained habeas relief from his continued incarceration, rather than on the date that the miscalculation was allegedly made. Federal appeals court overturns dismissal of lawsuit as time-barred. Erlin v. U.S., No. 00-16986, 364 F.3d 1127 (9th Cir. 2004). [PDF]

U.S. government could not be held liable under Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA), 28 U.S.C. Secs. 1346, 2671 et seq., for alleged negligent care provided to a federal prisoner by a doctor who was an independent contractor rather than an employee. Statute does not authorize lawsuits against the government for the actions of independent contractors. Jones v. U.S., 305 F. Supp. 2d 1200 (D. Kan. 2004).

Filing Fees

Wisconsin inmate incarcerated in an out-of-state facility was not a "prisoner" eligible under Wisconsin state statute for a waiver of court costs and filing fees and his claim for further review of denial of his request for a change in his security status and transfer to a lower security facility therefore could not be pursued. State Ex. Rel. Labine v. Puckett, No. 02-2642-W, 676 N.W.2d 424 (Wis. 2004). [PDF] (Also available in .html format).

Medical Care

Evidence did not show that prison officials acted with deliberate indifference to detainee's need for medical treatment for his psoriasis when he was seen by prison doctors on seven separate occasions during his five months at the facility, and seen by nurses at least fifteen times, as well as being transported to off-site specialists, including his own rheumatologist and dermatologist on over twenty occasions. Many of the prisoner's specific complaints "relate to the quality of care he received rather than to the lack of care," which did not show deliberate indifference by the officials. Kramer v. Gwinnett County, Georgia, 306 F. Supp. 2d 1219 (N.D. Ga. 2004).

Prison Litigation Reform Act: Exhaustion of Remedies

Prisoner failed to exhaust available administrative remedies as required by 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1997e(a) before filing a lawsuit concerning prison officials' alleged deliberate indifference to his medical needs concerning his feet and footwear. While he did file a prison grievance, he did not mention these officials in the first step of his grievance procedure. Vandiver v. Martin, 304 F. Supp. 2d 934 (E.D. Mich. 2004).

Prisoner Assault: By Officers

Correctional officers were not entitled to qualified immunity from excessive force claim by previously brain-damaged pre-trial detainee who they allegedly caused severe facial and head injuries in the course of a struggle to apply restraints to his wrists after he refused to get on the water-covered floor of his cell. Detainee's behavior of banging on cell walls and doors and tossing toilet water around his cell to "protest" not being allowed out of his cell, however, was not "protected speech," so that detainee's First Amendment retaliation claim was dismissed. Simms v. Hardesty, 303 F. Supp. 2d 656 (D.Md. 2003).

Prisoner Death/Injury

Prisoner who claimed that he slipped and fell on a wet floor in a Pennsylvania state prison, injuring himself, could not collect damages. State correctional department was entitled to summary judgment because a wet or waxed floor was not a "dangerous condition" sufficient to come within an exception to sovereign immunity under state law for defects in real property. Raker v. Pa. Dept. of Corrections, 844 A.2d 659 (Pa. Cmwlth. 2004). [PDF]

Prisoner Discipline

Disciplinary committee's decision denying accused inmate's request for production of a videotape of the alleged disciplinary incident in which he was accused of using abusive language was improper, in the absence of any factual finding that the videotape would be irrelevant or that production would be either hazardous to prison safety or a violation of some statute or rule. Barnes v. Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, No. A-02-797, 676 N.W.2d 385 (Neb. App. 2004). [PDF] (Also available in .html format).

Imposition of discipline on prisoner based on staff reports, the prisoner's own statement, letters written by the prisoner, and an investigation report satisfied due process requirements, and disciplinary board provided an adequate explanation of its reasons for refusing to allow the prisoner to call a live witness because the witness had been determined to be a threat to institutional security. Thomas v. McBride, 306 F. Supp. 2d 855 (N.D. Ind. 2004).

The fact that witnesses refused to testify did not violate the prisoner's right to call witnesses in a disciplinary proceeding. Hearing officer also adequately assessed the credibility of confidential information through a detailed exchange with a correctional officer and was not required to himself interview the confidential informant. Berry v. Portuondo, 775 N.Y.S.2d 110 (A.D. 3rd Dept. 2004). [PDF]

Disciplining of prisoner for alleged assault on another inmate in a new disciplinary proceeding approximately a year after he had been found not to be the perpetrator in a prior proceeding was improper, as the issue was previously decided. An intercepted letter by the victim of the assault, which was ambiguous, was insufficient to constitute newly discovered material evidence sufficient to depart from this principal and reopen the case. Hernandez v. Selsky, 773 N.Y.S. 2d 178 (A.D. 3rd Dept. 2004). [PDF]

Prisoner Suicide

Pre-trial detainee's prior placement on suicide watch, and other prior incidents, including him cutting himself, did not suffice to show that jail officials were deliberately indifferent to the possibility of his attempting suicide by placing him in the general population, when a medical judgment had been made that this was now appropriate. There was nothing to show that jail officials were subjectively aware of a substantial risk that the detainee would imminently attempt suicide. Detainee therefore could not seek damages for injuries suffered in unsuccessful suicide attempt. Strickler v. McCord, 306 F. Supp. 2d 818 (N.D. Ind. 2004).

Claim that jail personnel who came into contact with a pre-trial detainee "should have" known that she was suicidal was not sufficient to state a claim for "deliberate indifference" to a known substantial risk of suicide as required for federal civil rights liability. House v. County of Macomb, 303 F. Supp. 2d 850 (E.D. Mich. 2004).

Privacy

Federal prisoner could not be awarded damages under the Privacy Act, 5 U.S.C. Sec. 552a(g)(4) based on his allegation that the Bureau of Prison's reliance on his criminal history, as reflected in a pre-sentence investigation report, constituted the intentional maintaining of inaccurate records. The prisoner did not challenge the accuracy of his past drug conviction, but rather to the weight it should have been given in determining his custody classification. Doyon v. U.S. Department of Justice, 304 F. Supp. 2d 32 (D.D.C. 2004).

Racial Discrimination

African-American prisoner's "conclusory allegations" that he was singled out for "being an inmate of the black race" and denied "the same rights enjoyed by white inmates" on numerous occasions, including in connection with medical care and transfer to administrative segregation were frivolous. He failed to point to any similarly situated white prisoners who received preferential treatment. Lawsuit was therefore properly dismissed as frivolous under 28 U.S.C. Sec. 1915A. Gadlin v. Watkins, #03-1313, 93 Fed. Appx. 204 (10th Cir. 2004).

Telephone Access

Trial court erred by dismissing class action lawsuit by inmates' family members, friends, and attorneys against Indiana sheriff claiming that contracts entered into with telephone companies caused excessive charges for accepting collect calls from inmates. Additional opinion clarifies that appeals court did not mean to imply, in original opinion, that the proceeds that the sheriff's department receives from phone companies under these contracts become the sheriff's personal property or that the sheriff was personally "pocketing" such funds, but merely that Indiana state statutes are "very precise as to what funds a sheriff can collect, where they go, how they should be spent, and how the funds should be tracked." Alexander v. Cottey, #49A02-0301-CV-32, 801 N.E.2d 651 (Ind. App. 2004), 806 N.E.2d 315 (Ind. App. 2004).

•Return to the Contents menu.

Report non-working links here

AELE's list of recently-noted jail and prisoner law resources.

U.S. military prisons overseas:

The Taguba Report on allegations of abuse at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. (Pentagon's investigation of the U.S. 800th Military Police Brigade).

Brigadier General Janis L. Karpinski's rebuttal to the Taguba Report investigating alleged prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. (Gen. Karpinski is the one-star general who was in charge of the prison). (April 1, 2004)

Class action racketeering lawsuit filed against two U.S. defense contractors accusing them of conspiring with federal officials to torture and abuse prisoners in Iraq, and doing so in order to increase the number or amount of federal contracts they would receive. (March 9, 2004). Al Rawi v. Titan Corp., #04-CV-1143, U.S. Dist. Ct., S.D. Cal. San Diego, Cal. [PDF]

Charges filed against four U.S. soldiers accusing them of abusing prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq: Cpl. Charles Graner, Staff Sgt. Ivan L. Frederick, II,Sgt. Javal S. Davis, Spc. Jeremy C. Sivits.

U.S. v. David F. Passaro (June 17, 2004) Indictment by a federal grand jury of a North Carolina CIA contractor for assault on and subsequent death of a prisoner held by the U.S. military in Afghanistan.

Working Group Report on Detainee Interrogations in the Global War on Terrorism (March 6, 2003). Excerpts from a memo by a group of Pentagon, Justice Department and civilian lawyers submitted to the U.S. government suggesting that international and U.S. legal prohibitions against torture might not apply to interrogations of detainees suspected of terrorist activity.

Other related links of interest:

Military

Lawyers

Uniform

Code of Military Justice

The

Law of War

Reference:

• Abbreviations of Law Reports, laws and agencies used in our publications.

• AELE's list of recently-noted jail and prisoner law resources.

Featured Cases:

Disability Discrimination: Prisoners -- See also Access

to Courts/Legal Info

Drug Abuse and Testing -- See also Strip Searches: Prisoners

Prison Conditions: General -- See also Death Penalty

Prisoner Death/Injury -- See also Prison Conditions: General

Prisoner Discipline -- See also First Amendment

Prisoner Discipline -- See also Segregation: Disciplinary

Work/Education Programs -- See also Racial Discrimination

Noted In Brief Cases:

Defenses: Issue Preclusion -- See

also Prisoner Discipline (4th case)

Defenses: Sovereign Immunity -- See also Prisoner Death/Injury

Defenses: Statute of Limitations -- See also Federal Tort Claims Act

(1st case)

Disability Discrimination: Prisoners -- See also Defenses: Statute

of Limitations (1st case)

False Imprisonment -- See also Federal Tort Claims Act (1st case)

First Amendment -- See also Prisoner Assault: By Officers

Frivolous Lawsuits -- See also Racial Discrimination

Inmate Funds -- See also Assessment of Costs

Mail -- See also Access to Courts/Legal Info

Medical Care -- See also Disability Discrimination: Prisoners

Medical Care -- See also Federal Tort Claims Act (2nd case)

Prisoner Assault: By Officer -- See also Attorneys' Fees

Prison Litigation Reform Act: Attorneys' Fees -- See also Attorneys'

Fees

Prison Litigation Reform Act: Exhaustion of Remedies -- See also Defenses: Statute

of Limitations (1st case)

Report non-working links here

Return to the Contents menu.

Return to the monthly publications menu

Access the multi-year Jail and Prisoner Law Case Digest

List of links to court websites

Report non-working links here.

© Copyright 2004 by AELE, Inc.

Contents (or partial contents) may be downloaded,

stored, printed or copied by, or shared with, employees

of

the same firm or government

entity that subscribes to

this library, but may not be sent to, or shared with others.